Chances are, you’ve had more than a passing conversation about online dispute resolution (ODR, for short) within the last year. Maybe you’re investigating ways to implement ODR and looking for signs that the technology is beyond the major pitfalls of early adoption. Well, cue the good news: resolving disputes while cutting costs, frustration, and inconvenience has gained real steam this past year. In fact, the use of online platforms is no longer considered particularly “pioneering” for resolving warrants or minor high-volume cases (small claims, property, traffic, parking, tax, etc.) that clog our court system.

Experts caution that ODR isn’t appropriate for every case type, and while that’s true, we’re seeing courts worldwide explore different ways that ODR technologies might help with legal matters of many shapes and sizes. The data from early adopter courts are promising and prompt questions like, “why wouldn’t we do that?” as they experience faster resolution, fewer defaults, improved cost collection, and happier customers. So much ODR activity is now percolating that the Joint Technology Committee (JTC) has published multiple Resource Bulletins to help you understand ODR, how and where it’s being used, and whether it makes sense for your court.

Leveraging ODR Technologies

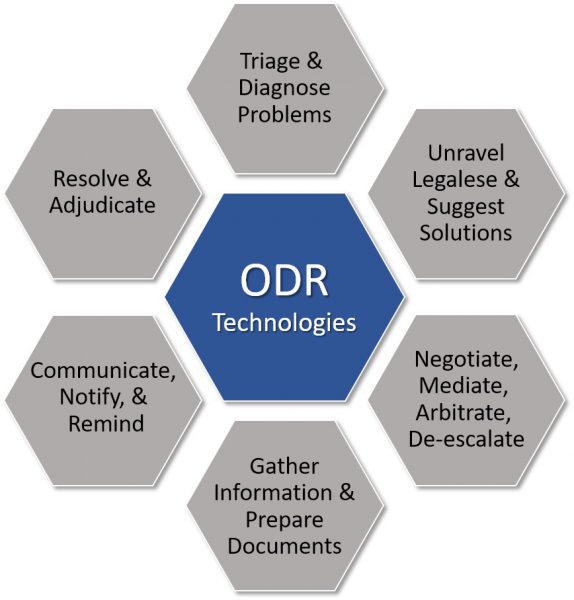

The JTC’s ODR for Courts Bulletin explains ODR technologies and their application to resolution processes and helps us frame ODR as “a thoughtful and intentional use of technology to facilitate problem resolution,” rather than a specific software package. The Bulletin goes on to say, “Any online case processing application that leads to resolution may be loosely described as ODR (focusing narrowly on the ‘online’” aspect versus ‘dispute resolution’). Technology can be used to automate some or all steps in a resolution process. It creates an additional path into the courts, expanding access to justice.”

Think about ODR as a collection of technologies that facilitate access to justice and problem resolution. Any cost associated with ODR technologies may be overshadowed by the cost of doing nothing. The Bulletin reminds us that “courts cannot maintain their current scale of operation with diminishing funding, or address an increasing scale with current funding.” Experts suggest that we think of savings rather than cost and that we include the value proposition for citizens in our plan. We can readily connect savings with the need for fewer resources or hearings, but often neglect to consider the “softer” savings realized when people are not incurring costs of travel, child care, or lost wages to pursue their legal matters with the court.

Early Adopter Case Studies

The JTC Resource Bulletin Case Studies in ODR for the Courts: A View from the Front Lines reviews various court experiences with ODR in Ohio, Michigan, Utah, New York, British Columbia, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands. Their results to date are quite encouraging; even the implementations that have fallen short of original goals have helped stakeholders better understand public challenges and technology uses. Courts and case types reviewed in the Bulletin include:

- Franklin County Ohio Municipal Court (small claims)

- Washtenaw County Michigan District Court (traffic, warrants)

- Ottawa County Michigan Circuit Court (family-court compliance)

- Utah Courts (small claims)

- New York Courts (consumer debt)

- British Columbia Civil Resolution Tribunal (residential property tax assessments, consumer protection, condominium disputes)

- UK Ministry of Justice (personal-injury claims)

- Netherlands (various civil, family)

The Bulletin covers these courts and their ODR projects in much more detail, including noteworthy accomplishments and cautionary tales. They each continue to explore opportunities for ODR by analyzing what’s working and what’s required to expand success in their courts. What’s becoming clear across the board? ODR can be a real game changer for courts that are willing to innovate.

Getting Started: Some Things to Consider

- Even cases that are not suitable for full-on ODR may benefit from certain elements. Consider whether any part of a dispute is resolvable online. Break the process down into pieces and perhaps automate some of them through ODR.

- Who is the appropriate audience for which models of ODR in your court? It doesn’t have to be an all-or-nothing approach; maybe ODR is used exclusively for certain cases and as an option for others. You will also need to consider whether ODR will serve parties who are self-represented and/or those with legal counsel and how that may affect certain processes.

- Think about how to make ODR available to as much of your audience as possible by including access via desktops, laptops, smartphones, or kiosks. Remember that the user experience must fit the device and the people most likely to use that device, so insist on solutions that are responsive to device and user nuances.

- Perhaps the most important consideration is ensuring that your ODR platform facilitates fair, just, and timely outcomes. It does no good to simply automate a frustrating or confusing process that doesn’t move the parties toward an agreeable resolution. Your ODR system must be intelligent enough to distinguish which cases can be resolved through ODR and which should take a more traditional path, no matter where they are in the process.

About the Author

Sue Humphreys is vice chair, IJIS Courts Advisory Committee.