It is time to improve the way we communicate information. In 2015 the Conference of State Court Administrators and the Conference of Chief Justices promulgated Joint Resolution #5, calling for the “aspirational goal of 100 percent access to effective assistance for essential civil legal needs.”1 Four years earlier, the United States Supreme Court, in Turner v. Rogers, held up court forms and self-help materials as emblematic of the important role that courts play in providing meaningful access.2

More than ever before, state courts have a clear obligation to effectively communicate procedures and other requirements to the users who come through the courthouse door. An ever-increasing number of court users are representing themselves. These are no small matters. Essential civil legal needs include shelter, economic security, and legal rights and obligations regarding children and family members.

Drafting Forms and Information: The Traditional Approach

While executive-branch agencies at the state and federal level have adopted rules requiring plain language, including the Plain Language Act of 2010 (H.R. 946), courts have been slow to implement such requirements.

The creation of forms and information within a court system is most often driven by the needs of the court itself. Court staff start from the perspective of what the judge, clerical staff, or case management system require to process a given case in accordance with laws and court procedures. Instructions and self-help materials start by addressing the legal substance and legal concepts at play, with an emphasis on defining legal terminology. A pamphlet about eviction, for example, might start by defining terms such as eviction, plaintiff, defendant, and notice to quit. Court forms often skip the definitions and simply provide spaces for people to insert information that is relevant to the judge or clerical staff. The court location is often the dominant text, followed by statutory language or other legal jargon. The result? Self-represented litigants who fill out the wrong paperwork, incorrectly, asking lots of help of court staff and judges, resulting in case delays and a negative court user experience.

An Alternative Approach

Rather than designing written materials based on the needs of judges and court staff, courts should approach written materials from the court-user perspective by asking, “What does the court user need to know about this case and court procedures to successfully take the next steps in the process?”

Courts do not have to reinvent the wheel. They can look to lessons learned from other fields. At the Access to Justice Lab at Harvard Law School (A2J Lab), researchers look to fields outside the law, including public health, psychology, and adult education. Rigorous evaluation in these fields has generated ample evidence of what works in getting adults to absorb and successfully deploy the information provided, which is, after all, the goal of providing information in the first place.

Use Plain and Direct Language

Whether in law, government, medicine, or other fields, the consensus around plain language is clear. Studies ranging from patients’ adherence to their prescription-drug regimens to voters at the ballot box all emphasize that plain and direct language increases understanding and application of information. Federal guidelines promote plain language so that users can:

- Find what they need

- Understand what they find

- Use what they find to meet their needs3

This is all the more important in explaining court processes. Studies of stress and psychological barriers to understanding highlight that even for those with high literacy and familiarity with a topic, stress can limit a person’s ability to digest and process information. People often come to court as a last resort, or after a crisis in their family, home, or workplace requires legal action. Plain and direct language can be crafted to overcome these barriers to ensure understanding and accurate completion of procedural requirements.

What Does Plain Language Look Like?

Shorter sentences. “The education literature recommends the use of short sentences. Very short. Perhaps so short that they lack subjects and verbs. Some that are not grammatically correct. Write the way the intended user speaks and thinks. Write as though you are competing for the time and attention of busy and stressed individuals. Because you are.”4

Change passive voice to active voice. For example, the sentence, “Court notice will be sent after answer is filed,” becomes, “File your answer. After you file your answer, the court will send you a notice of your court date.” Official court language frequently uses passive voice to avoid addressing the reader directly. Instead, courts should address the court user directly. Including the word “you” can make instructions shorter and clearer.

Take this example from the executive branch:5

Before

“When the process of freeing a vehicle that has been stuck results in ruts or holes, the operator will fill the rut or hole created by such activity before removing the vehicle from the immediate area.”

After

“If you make a hole while freeing a stuck vehicle, you must fill the hole before you drive away.”

Aim for a sixth-grade reading level. While not clear proof of direct and precise language, automated reading-level tools are helpful proxies. Free websites exist that rate text for readability, including reading level, sentence complexity, word use, and passive voice.

Consider the Look and Feel of the Document

In addition to the words themselves, the format of words on a page has a significant impact on a person’s ability to digest and act upon the information presented.

Capitalization. The clearest lesson from the literature is to avoid ALL CAPS at all costs.6 Readers tend to skip words and sentences where all letters are capitalized, meaning that the most important information is the least likely to be read.

White space and headings. Overall, the less text and more white space on a page, the easier it is to digest and understand. The goal of reducing the number of pages often comes at the expense of white space, but effective forms and self-help materials can balance these two needs. Plain-language consultants at Transcend Translations also recommend numbering sections and adding clear descriptive subheadings on the page to help the reader understand each section in context.7

Typeface. Experimental findings suggest that the typeface (serif or sans serif) does not affect comprehension.8 That said, there are practical considerations when choosing a typeface. Court staff often resort to photocopying rather than printing new forms directly, resulting in fuzzy or blurry text. With that in mind, sans serif (rather than serif) fonts are a better choice, as they result in cleaner photocopies.

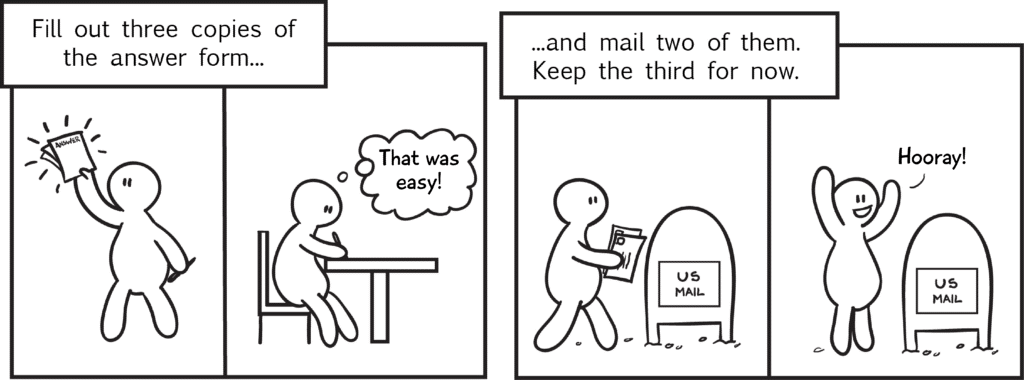

Visuals. Illustrations that relate to the text increase the likelihood that someone will follow the instructions.9 Effective visuals can sometimes replace lengthy text instructions. For example, the instruction, “Once you have received the complaint, mail copies of your Answer to both the Plaintiff and the Court. Retain a copy for your own records,” can be visually depicted.

In addition to cartoons, other visual representations of information include road maps and flowcharts. The key is to provide a visual that clearly conveys information in a way that the reader can understand.

Before

After

Emphasize Procedural Knowledge Over Conceptual Understanding

A2J Lab researchers work with practitioners to develop and test new interventions, including court forms and self-help materials. The first step in our approach is to identify the legal problem or court process then break that process down into all of its parts. For example, when an individual comes to the courthouse or court website looking for information on how to defend a small-claims case, what are the steps that a person must take to defend the case? Explaining these steps does not require legal advice or even legal information. Most of these steps are logistical, administrative “legal mundanity.” How many copies should the person make of their court papers? Where do they go when they first come to the courthouse? Do they need to check in with anyone? Where do they sit while they are waiting? How long should they be prepared to be at the courthouse? Most court notices and instructions overlook some of these steps as they have little to do with formal law. But, from the perspective of the court user, they are both critical to the process and completely unknown without court guidance.

Affirmation and Motivation

As Professors Greiner, Jiménez, and Lupica describe in their article “Self-Help, Reimagined,” “Modern self-help materials fail to address many psychological and cognitive barriers that prevent the individuals who use them from successfully deploying their contents.”10

Breaking a court process down into its constituent parts for the court user might include:

- overcoming fear or intimidation about the court itself

- making a plan to come to court

- gathering and understanding information about what will happen at court

- preparing for what will happen

- following through

For instructions to be effective, readers must feel they are achievable. Studies show that increasing feelings of self-efficacy increase the likelihood that a person will take a recommended course of action.11 Research suggests that providing instructions on what specific actions to take to deal with a stressful situation can be effective, for example, by providing a specific action plan for getting flu shots.12 Specific, proximate goals or action steps can increase a patient’s success in managing a medical condition.13 They may also increase a court user’s success in navigating complex court procedures. Is this outside the scope of a court’s obligations? Not at all! In fact, a notice of trial or other notice to appear is specifically intended for the recipient to read and to follow the course of action—to come to court. If a party does not come to court, the adversarial process grinds to a halt, and in many jurisdictions, time and money are spent on alternatives to force the party to attend (e.g., civil arrest warrant).

Modify Court Process

Forms reflect process. Sometimes, all the plain-language description in the world cannot save a process from being unnecessarily complex. Using the form itself as a starting point, court administrators can look at the process from the perspective of the court user.

Test to See What Works

User testing is useful when developing a new written tool. Consider conducting interviews, focus groups, or surveys of people who use the information. User testing at its best is an iterative process and an inclusive one. Users can include litigants, lawyers, interpreters, and clerical staff. Iterative feedback from court users can improve the result and highlight underlying court processes that can be simplified.

After initial user testing, it is important to build rigorous evaluation into the rollout of any new intervention, including new court forms. The most scientifically rigorous evaluation technique is a randomized study. This means rolling out a new intervention in a randomized fashion, with a control group (status quo) and a treatment group (the group that receives the new form).

Partner with Researchers

Courts can partner with researchers like the A2J Lab to design new interventions and to evaluate their impact. In a recent study, A2J Lab researchers partnered with courts and other stakeholders to assess whether improved self-help materials can improve litigants’ success in navigating procedural hurdles.

Case Study: Reducing Default in Debt-Collection Cases

In jurisdictions across the country, as many as 95 percent or more of debt-collection defendants lose their cases because they do not show up to court, even when they have a strong chance of winning their cases. How can legal-service providers and courts persuade individuals to participate in the legal process?

Lab researchers partnered with courts and legal-aid organizations to address this question in the context of consumer debt. Our pilot study demonstrated that a well-constructed letter sent to debt-collection defendants at the start of their case can more than triple the rate of defendants coming to court to contest their cases.14 We are currently expanding the study to test the effectiveness of images and translation as elements of a well-constructed letter.

About the Author

Erika Rickard is a researcher at the Access to Justice Lab at Harvard Law School. The Access to Justice Lab is on a mission to transform U.S. law into an evidence-based profession by implementing and publishing rigorous, empirical studies to create credible evidence about what works and what does not in access to justice and court administration.

Notes

- “Resolution 5: Reaffirming the Commitment to Meaningful Access to Justice for All,” adopted at the annual meeting of the Conference of Chief Justices and Conference of State Court Administrators, Omaha, Neb., July 2015.

- Russell Engler, “Turner v. Rogers and the Essential Role of the Courts in Delivering Access to Justice,” Harvard Law and Policy Review 7 (2013): 31.

- “Federal Plain Language Guidelines” (March 2011; rev. May1, 2011), p. 94.

- D. James Greiner, Dalié Jiménez, and Lois Lupica, “Self-Help, Reimagined,” Indiana Law Journal 92 (2017): 1119, 1135.

- Before and after examples taken from the Plain Language Action and Information Network (PLAIN).

- Ruth Anne Robbins, “Painting with Print: Incorporating Concepts of Typographic Layout and Design into the Text of Legal Writing Documents,” 4. Journal of the Association of Legal Writing Directors 2 (2004): 108, 115.

- Maria Mindlin and Katherine McCormick, “Plain Language Works for Pro Per Litigants,” Transcend Translations, Davis, Calif. (2012).

- Maria Lonsdale, May C. Dyson, and Linda Reynolds, “Reading in Examination-Type Situations: The Effects of Text Layout on Performance,” Journal of Research in Reading 29 (2006): 433-53.

- Peter S. Houts et al., “The Role of Pictures in Improving Health Communication: A Review of Research on Attention, Comprehension, Recall, and Adherence,” Patient Education Counseling 61 (2006): 174, 175; W. Howard Levie and Richard Lentz, “Effects of Text Illustrations: A Review of Research,” Educational Communication and Technology 30 (1982): 195, 206 (analyzing 155 studies on the effect of illustrations on reading comprehension); J. M. H. Moll, “Doctor-Patient Communication in Rheumatology: Studies of Visual and Verbal Perception Using Educational Booklets and Other Graphic Material,” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 45 (1986): 198, 202.

- Greiner, Jiménez, and Lupica, supra n. 4, p. 1119.

- James E. Maddux and Ronald W. Rogers, “Protection Motivation and Self-Efficacy: A Revised Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change,” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 19 (1983): 469.

- Kevin D. McCaul and Rebecca J. Johnson, “The Effects of Framing and Action Instructions on Whether Older Adults Obtain Flu Shots,” Health Psychology 21 (2002): 624, 627.

- P. G. Gibson and H. Powell, “Written Action Plans for Asthma: An Evidence-Based Review of the Key Components,” Thorax 59 (2004): 94, 94-95.

- D. James Greiner and Andrea Matthews, “The Problem of Default, Part I,” available at SSRN (June 21, 2015). Learn more about the project at the Access to Justice Lab, Harvard Law School.