Having previously considered the difficulties most courts have in achieving and sustaining high performance and the ways to realistically approach performance improvements, we now focus on building human capital. Developing the individual and collective competencies of those who work in an organization is a critical component of any organization’s capacity to improve. Workforce development is the conscious effort to build human capital. However, as argued in the first of this two-article series,1 professional development programs in the field of court administration may not meet court needs—contributing to the challenges courts have in improving their performance.

Court administrative performance will not improve absent courtwide workforce development. It is not enough to develop the competencies of those in managerial positions. High performance requires that clerical staff know more than just the technical requirements for processing payments and pleadings. Similarly, judges must understand and apply principles for caseflow, workflow, and workforce management in addition to those involving the adjudication of cases.

Even in good fiscal conditions, workforce development budgets in courts tend to be lean. When budgets must be reduced, training funds are often among the first that are cut—even though such times are arguably the ones in which a court has the greatest need to optimize the performance of existing staff. Making matters worse, courts seldom make the most of what training funds they have. As related in the first article of this series, neither the practices by which trainees opt-in nor the design of training programs are optimized to deliver effective development to the greatest number of court personnel which resources would allow.

All court personnel, from entry-level staff to judges, should develop basic court management competencies appropriate to the level and range of responsibilities for each position.

Workforce development programs need to be designed to provide the necessary level of competency to as many court personnel as possible given available funds. Furthermore, such programs should be designed in accordance with adult-learning principles with follow-up steps to improve retention of training lessons. The average court manager, particularly in small and medium-sized courts, does not have the background to identify their own competency needs, let alone those of all judges and staff. Managers also lack the backgrounds to assess the suitability of given training programs for meeting developmental needs. They need more guidance and support.

Understanding Specific Problems with the Traditional Development Approach

Many problems with current professional development efforts among the courts are the same ones found in most professional development programs. Recent findings from neuroscience research explain truths that have long been understood in organizational management. Trainers in the business world have learned that students, on average, forget 70 percent of what they are taught within 24 hours of a training event. Studies suggest that to retain capacity for future learning, our brains have evolved to forget information naturally over time unless something signals that the information is important. Whereas our ancestors might have received immediate feedback in the form of rewards (e.g., food or pleasure) or harm (e.g., pain/injury/perception of danger), our modern learning environments—particularly ungraded workplace training—do not tend to include such signals of importance. It is possible, however, by providing a series of booster events (e.g., tests, refresher summaries, or opportunities to apply lessons) in the hours and days after training, to reset the forgetting curve each time and to maximize long-term recall.2

Beyond the limitations that the forgetting curve imposes on general workplace training, the curve is only one factor among several that explain why most leadership development programs are not preparing effective leaders or increasing performance. Robert O. Brinkerhoff, an expert in evaluation and learning effectiveness, has identified three main reasons why 80 percent of training interventions fail to produce notable change:

- Inadequate follow up—the participating managers are not supported in applying what they have learned;

- Lack of engagement of participants’ managers before the training event—without which there is no certainty that the training is focused on the right learning outcomes (e.g., accomplishing behavior changes that improve performance versus satisfying compliance requirements, adding bench [reserve] strength, fulfilling required certifications, or simply providing a résumé-building perk); and

- Overemphasizing investment in the quality of the learning event versus its intended outcome.3

Similarly, Nick Petrie of the Center for Creative Leadership has identified four problems with leadership and management development programs:

- Programs spend too much time delivering information and not enough on the hard work of developing the leaders themselves. Most leaders already know what they should be doing; what they lack is the personal development to do it.

- When leaders return to work, they are overwhelmed by tasks. They find difficulty in converting what was learned into actions that address real problems.

- In addition, most programs fail to engage the learner’s key stakeholders back at work. As a result, leaders not only miss out on the support, advice, and accountability of colleagues, but also often experience resistance from constituents who are surprised and disrupted by any changes participants make in their behavior.

- Leadership development programs are designed as events rather than as processes over time. Programs give learners a short-term boost but not the ongoing follow-up to transform newly learned behaviors into long-term habits.4

Organizations must become better at clarifying the purposes for training, improving retention of what is learned, and communicating and applying lessons to organizational behaviors.

The Need for Sound Job Classification and Workforce Development Frameworks

In the fullest sense, talent management is the entire scope of human resources (HR) processes to attract, onboard, develop, engage, and retain high-performing employees.5 Among courts, the responsibility for this range of human capital acquisition and development functions does not fall strictly on HR staff but may be spread among managers in the local courts, as well as staff in various departments of state-level administrative offices. The division of developmental responsibilities may also depend on the size of a court, with larger trial courts and more centrally administered court systems being more likely to have staff dedicated to talent management than smaller courts and decentralized systems. In the ideal, courts will have a current and objective classification system, which defines the duties of different court positions and the minimum capabilities required to perform each job; such a system will guide recruitment processes, performance reviews, promotions, etc. Paired with such a classification system, courts need a talent management program (TMP)—an intentional, ongoing process for workforce development.

To guide recruitment, performance reviews, promotions, etc., courts need a current and objective job classification system that defines the duties of different court positions and the minimum capabilities required for each job. Paired with such a classification system, courts also need a talent management (TMP) — an intentional, ongoing process for workforce development.

Job Classification Systems

HR and management consultant Susan M. Heathfield defines “job classification” as “a system for objectively and accurately defining and evaluating the duties, responsibilities, tasks, and authority level of a job.”6 Done well, she explains, job classification should create “parity in job titles, consistent job levels within the organization hierarchy, and salary ranges that are determined by identified factors.”7 Among these factors are:

- market pay rates for people doing similar work in similar industries in the same region of the country,

- pay ranges of comparable jobs within the organization, and

- the level of knowledge, skill, experience, and education needed to perform each job [emphasis mine].8

To create a well-defined comparison, a job classification system usually works with a structure of job functions, families, and positions. One of the purposes of job families is to provide a foundation for strategic workforce planning and development to meet an organization’s needs and priorities. Every job is part of a job family, and every job family is part of a function. Within such a structure, job classification should make intuitive sense and enable swift categorization of existing and potential new jobs whenever relevant.9

As Laura Griffin found in her award-winning research for the ICM Fellows Program, research on court-specific employee positions is scarce as compared to what has been written about court performance, case processing, and the need for qualified and well-compensated judges.10 Ms. Griffin’s research compared job duties and compensation in Virginia’s two trial court levels (circuit and district), the Maryland judiciary, and the federal judiciary. Although she found major differences among jurisdictional and statutory tasks, the overall duties and the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) required to perform jobs among the trial courts were very similar.11 Furthermore, it would be safe to assume that a comparable study across trial courts nationally would have similar findings. Indeed, the basic premise underlying the competencies of NACM’s Core® is that, despite there being differences in levels of job responsibilities within courts, there are similar functions and job families across the nation’s courts for which there are common sets of KSAs not only for court “professionals” but also for anyone working in the field of court administration whose efforts contribute to court performance.

With this understanding, it should be possible to develop an array of workforce development programming for comparable ranges of jobs within courts throughout the United States, which draws upon the Core® curricular resources. What is missing are consistent and objective classification frameworks among state court systems to simplify the identification of what workforce development programming is appropriate to specific jobs. To some degree, the lack of comparable classification frameworks is a result of the significant variation in court system governance and structure among states. In municipal courts and courts within decentralized state systems, court jobs may be subject to local government classifications that are ill-suited to court responsibilities. Even in more centralized systems, such as Virginia’s, classification frameworks may be inconsistent among trial courts at the same level, let alone between courts at different levels. Finally, even in courts with developed comprehensive classification systems, problems may arise over time if those systems are not adequately monitored and maintained to account for changes, such as some court jobs becoming more professional and technical over time rather than clerical. As Jeffrey Crenshaw and Roger McCullough explain, to the extent that a classification system has been adversely impacted by unplanned and unaccounted for change, not only selection procedures but also performance appraisals, employee development, and compensation initiatives can be compromised.12

Talent Management

Roughly a decade ago, then NACM President-elect Kevin J. Bowling said, “I believe we as court leaders have a duty to invest in our profession and a fundamental responsibility to prepare our courts for the future. A talent management program, albeit challenging to implement, is one effective approach to doing both.”13 Of course, Bowling also observed, “It seems the daily crush of court business coupled with the lack of adequate training resources results in most court managers ignoring the need for systematic talent development and talent management.”14

Whether the goal is to improve onboarding of new employees, develop basic leadership skills, or target succession planning needs, the key is to employ an intentional, ongoing process for workforce development.

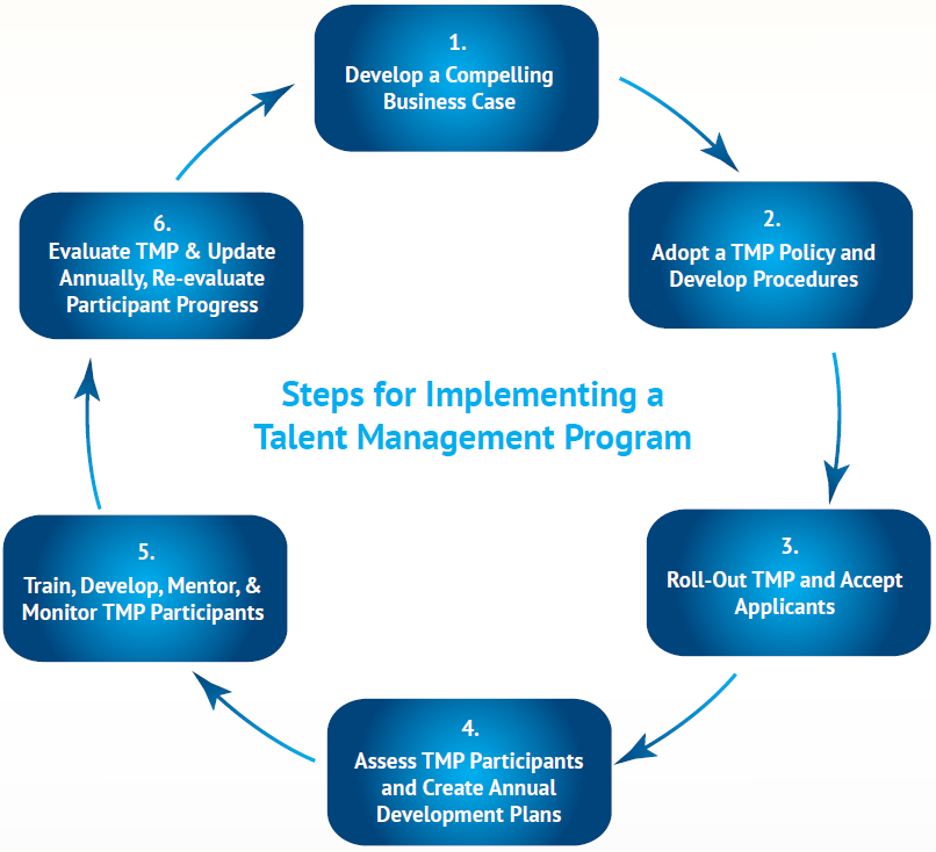

Thankfully, there are already TMP models for courts that can be studied and adapted to state and local court system needs. An ongoing approach is needed whether a program serves a single court (large or small) or whether it serves a larger jurisdictional region or even an entire state. Obviously, the larger the scope, the greater the number and types of positions that may be involved. Brenda J. Wagenknecht-Ivey, who has contributed to the most notable court-related TMP literature,15 recommends steps by which courts should implement TMPs (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Source: Brenda J. Wagenknect-Ivey and Jacqueline Zahnen Cruz, Resource Guide: Establishing a Succession Planning/Talent Management Program, p. 8.

As in so many change management contexts, objective data are important from the beginning to enable informed decision making and to create a sufficient sense of urgency that will convince leaders to support the necessary changes in policy and procedures that a TMP will require. One key element in implementing a TMP is the development of competency models,16 which are the personal characteristics and behaviors that are linked to achieving (or failing to achieve) excellent performance in key positions. Importantly, these competency models are distinct from the KSAs needed to perform particular functions or those within specific jobs—KSAs should be components of a separate, objective job classification system. Fundamental competencies—applicable to all court personnel—include integrity/honesty, personal effectiveness, and interpersonal/communication skills. Managerial competencies include building effective relationships, leading and managing people, and strategic thinking.

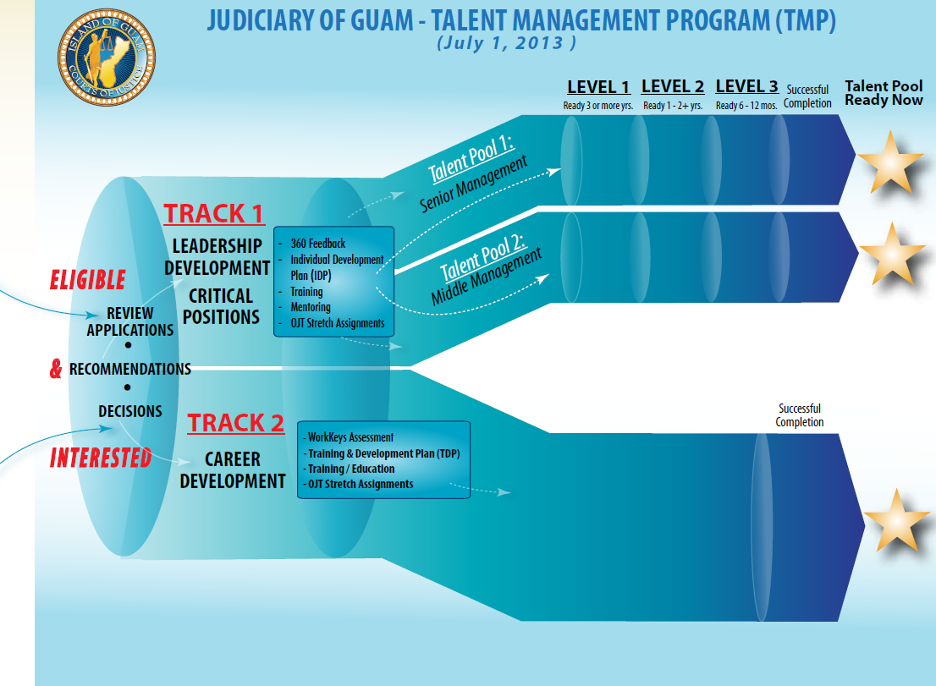

Figure 2

Talent Management Program Logic Model

Figure 2 is a visual representation of a TMP that was developed by the Judiciary of Guam. It illustrates the following important principles:

- The TMP is open to staff who are interested, meet the eligibility requirements, and [are] willing to complete the application process.

- Because the TMP is a special program for an organization’s high achieving, high potential staff, there is a critical review process. Applications are reviewed by a TMP Team, the TMP Team makes recommendations for acceptance into the TMP, and the Judiciary’s top leadership makes the final decisions.

- Applicants apply for and are accepted into one of two tracks. Track 1 focuses on developing the next generation of senior leaders and middle managers. Track 2 provides the organization’s staff with additional career and professional development opportunities.

- Each track includes an assessment and preparation of an individual development plan consisting of formal education and training, on-the-job development, and mentoring. The development path is monitored and updated as needed until participants complete the developmental requirements.17

Admittedly, having a model and being able to adapt and implement a TMP for one’s court organization are not the same thing. Even though the TMP literature acknowledges the different scale and scope of effort required for TMPs in small versus large courts, that does not mean court managers in small rural courts or municipal (non-state) courts find the demands of a TMP within their capacities, assuming they are even convinced that a TMP would be worthwhile. Furthermore, the scarcity of such programs even in larger courts and court systems indicates that TMPs are either not recognized as important or are heavy burdens even for them. If conditions are to improve, greater advocacy and supportive resources are needed for TMPs and general workforce development.

If conditions are to improve, greater advocacy and supportive resources are needed for TMPs and workforce development generally.

Recommendations

Improving workforce development in the courts will require a comprehensive, collaborative approach, which leverages the strengths of a range of contributors both to develop solutions, which will have the flexibility and adaptability to work across a variety of court systems and to enable options that would not otherwise be possible given resource limitations. There are roles for national, regional, and state professional associations; national and state institutional programs; and new partners.

-

Develop a model job classification system for courts and a process to keep it up to date.

Creating a basic framework of job functions, families, and positions that could be easily adapted to most courts, large or small, and being able to update that basic model should reduce the future work that would otherwise have to be replicated by states or individual court jurisdictions to keep classification systems relevant. Greater uniformity in job classifications should support common workforce development standards.

- Assist courts in adapting and implementing TMPs—including pairing them with what will become more uniform job classification systems.

A TMP should:

- Enable court managers to establish clear understanding of the training objectives for any individual participant, the court, and the larger court system, incorporating effective performance analysis to ensure that any gaps between current performance and desired performance can be filled by training and development.18 Objectives might include allocation of time after training events to consider, apply, and pass along lessons to others.

- Ensure that participants can see a clear correlation between what they are learning and real-life needs—for example, if staff need skills in applying a NACM competency rather than knowledge of the competency, an appropriate course will focus on that skills gap. The format of any course would be as short and to-the-point as possible.19

- Simplify the development and delivery of educational programs/courses nationwide that are appropriately tailored to different ranges of court jobs.

- Create a common, objective basis for testing individuals’ development of KSAs and competencies (applicable in the context of recruitment, compensation, promotions, and even professional certifications) and for assessing the effectiveness of training programs.

Collaborate to offer more cost-effective workforce development to a greater number of court employees.

Achieving broad and meaningful workforce development will require coordinated developmental efforts that draw upon the strengths and advantages of different stakeholders (e.g., courts, judicial educators, and professional associations) and employ a variety of training methods/media. The appropriate approaches will vary according to the size and structure of court systems and the type of training needed.

Professional associations at the state, regional, and national levels should help in identifying the KSAs appropriate to different court responsibilities, develop programs and products to introduce court employees to concepts within subject-matter competencies, and provide opportunities for networking and mentorships.

NACM’s proposed Core Champion program20 is an example of a development effort that could introduce members and others in the field to the range of competencies that would-be court leaders need to develop. Although not foreseen as an in-depth educational series, the Core Champion program might encourage individuals to pursue further levels of education and professional development.

- National and state educators need to be more actively engaged with courts in designing and adapting curricula for different types of court jobs.

Both the creation and delivery of educational programs present cost challenges. For higher-level positions, the current educational model is largely one of developing generic courses focusing on each core court competency and building toward an individual certification credential. This model may be cost-effective for the curriculum development process when offered on a large scale; however, its products are not tailored to the specific needs of courts or individuals. Furthermore, despite an increasing number of online educational offerings, too many programs still require expensive travel to in-person courses.

Some traditional classroom training is still necessary, particularly for executive-level development in which valuable peer interaction might otherwise be difficult to arrange; however, offsite classroom instruction will never be an adequate model to expand development opportunities for most court personnel. From a standpoint of time and money, it would be impractical to send all employees through the 120 hours of classroom instruction required for a certification akin to that of ICM’s Certified Court Manager (CCM), and, frankly, most court employees do not need 2.5 days of training in every Core® competency. That is why educators need to engage with state and local court leaders to develop different levels of curricular content and more options for presenting it.

Local courts and state court administrative offices (AOCs) should develop plans for how each will contribute to workforce development.

Individual courts and AOC staff may already have an informal division of labor with state and national course providers in terms of workforce training, but in the absence of meaningful classification systems, competency assessments, and coordination, such training efforts may be misdirected or ineffective. With meaningful job classifications and TMPs, workforce development responsibilities can be more deliberately divided. Local courts can obviously provide valuable in-person training, such as during the onboarding process, but they may need state-level guidance so that onboarding will be more consequential than a mere new employee orientation.21 AOC staff can help organize regional training sessions serving staff in multiple courts, as well as statewide training, both in-person and online. The key will be to offer a variety of tailored courses that are:

- meaningful to different types of employees;

- low-cost;

- respectful of available employee time; and

- designed for high levels of engagement and retention.

Such tailoring of curricula may be where the expertise of state and national educators can be most valuable, regardless of who delivers the content.

Ensure that training programs reflect tested educational principles, e.g.:

- Incorporate several different ways to learn in recognition of people’s different learning styles and to keep them engaged.

- Break educational content into small units that are easier to absorb and retain. Focusing on one concept or skill at a time and then immediately allowing the learner to recall and to practice it afterward is one developmental approach that can be done well in sessions at a courthouse and online. This approach is not cost-effective in the dominant off-site model.

- Repeat content in different formats, both in delivering the content and in having participants practice its use. Programs should also encourage participants to summarize what they have learned in their own words.22

- Both during and in the days after training, use quizzes, polls, games, and other reinforcement techniques to emphasize what is important and improve retention. Many of these techniques can be very effective in eLearning formats.

- Finally, encourage individual courts to take part in some training programs as court teams—including a judge, when appropriate—so the participants can discuss and explore content together, considering how it might be specifically applied in their workplace.23

In the interest of economy and adaptability, invest more in high-quality, modular training units, which can be delivered online.

Ideally, there might not only be comprehensive sets of modules that would fully cover any competency, not unlike an ICM course, but also shorter or simpler sets of modules to address the educational needs of different court system employees, from entry-level clerks to judges, while also respecting the time they have available for study. For instance:

- A new deputy clerk might be offered a set of modules addressing the basics of several competencies, such as the purposes and responsibilities of courts, caseflow and workflow management, and accountability and court performance. Such a set might require about six hours to complete, not counting retention-assisting follow-ups.

- A new judge might be directed to a different set of modules emphasizing elements of workforce management and leadership in addition to fundamentals of caseflow and workflow management and accountability and court performance.

To get some of the benefits of classroom interaction, require that individuals who complete sets of online, recorded modules also take part in synchronous or asynchronous online discussions led by certified faculty before any educational credits are awarded.

For all trainees, including individuals who do take traditional, in-person classes, incorporate online modules and discussions into the training as follow-up elements to encourage retention and application of lessons.

Partner training providers with institutions and associations to develop low-cost, in-court consulting options to assist individuals and their court organizations in the application of developmental lessons.

If the costs of basic instruction could be lowered per participant, courts might have more funds to devote to such site-visit follow-ups, assuming that an AOC or association network could not provide such assistance at no charge.

Implementing a new model for workforce development will not happen overnight. Delivering quality programming at greater scale and economy while also tailoring it to local and individual needs is a major challenge. Longtime leaders in court professional development, such as ICM and NACM, will continue to play important and perhaps even expanded roles.24 Nevertheless, they cannot meet the challenge on their own. With the assistance of new partners, the court community can use eLearning tools to develop content that will reach more people at lower costs.25 At the same time, state judicial educators, technical assistance teams from AOCs, and state professional associations will need to play a greater role in adapting developmental offerings to specific court needs.

Conclusion

Court performance has significant room for improvement, and workforce development is a critical factor in making that improvement happen. Current workforce development for courts is based on some high-quality resources and providers—especially for managers—but developmental offerings are still inadequate for what courts need. In part, programs that teach the essential competencies for court management simply do not reach enough court personnel, but a bigger problem is that the career and court performance returns of existing programs are questionable. Court-training budgets are always going to be limited. So, existing programs should be revised, and new ones developed to maximize developmental benefits. Court education programs need not only to reach more people but also to better target their specific competency needs (individual and organizational) and whether those needs be for knowledge or the skills to apply it. Furthermore, programs need to use methods that will encourage participant engagement during instruction and retention and application of lessons afterward. Expanding the delivery of educational programming and appropriately tailoring lessons to individual and organizational needs will require much greater involvement by state and local associations, trainers, and advisors. Instructional techniques and online tools exist to support these efforts, and there is room for the contributions of both long-time leader and newcomers in the field. Reforming courts’ workforce development model is part of the solution to the high performance court challenge.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Kenneth G. Pankey, Jr., is the senior planner, Department of Judicial Planning, Office of the Executive Secretary, Supreme Court of Virginia, and a NACM director. Opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not represent the official position of NACM or the Virginia court system.

- Kenneth G. Pankey, Jr., “Professional Development in Court Administration: We Need to Do Better,” Court Manager 35, nos. 3-4 (2020-21).

- Art Kohn, “Brain Science: Overcoming the Forgetting Curve,” Learning Solutions Magazine, April 10, 2014.

- Richard McCarthy, “Why Leadership Development Programmes Don’t Work,” OMT Global Blog, August 31, 2017, summarizing Brinkerhoff’s work; see also, Robert Brinkerhoff, “Learning: Nice to Have or Indispensable Business Asset?” Chief Learning Officer, February 5, 2015.

- McCarthy, id., summarizing Petrie. See also Nick Petrie, “Future Trends in Leadership Development,” white paper, Center for Creative Leadership, Colorado Springs, 2014, at https://www.nicholaspetrie.com/.

- “Creating a Talent Management Strategy—the Full Guide,” DigitalHRTech.

- Susan M. Heathfield, “What Is Job Classification and How Do Employers Use It to Pay Staff?” The Balance Careers, blog, updated November 29, 2019.

- Id.

- Id.

- Erik van Vulpen, “Job Classification: A Practitioner’s Guide,” Academy to Innovate HR (AIHR), blog.

- Laura G. Griffin, “Ensuring Classification and Compensation Parity in Virginia’s District Courts,” paper, ICM Fellows Program, May 2019, p. 31. Ms. Griffin’s paper received the Class of 2019 Vice President’s Award of Merit for Applied Research.

- See id. Most relevant are findings 6 (p. 84), 9 (p. 89), and 11 (p. 92).

- Jeffrey Crenshaw and Roger McCullough, “Managing Change in a Job Classification System,” in Ronald R. Sims, ed., Change (Transformation) in Government Organizations (Charlotte: Information Age Publishing, Inc., 2010), p. 123.

- Kevin J. Bowling, as quoted in Brenda J. Wagenknect-Ivey, “From Succession Planning to Talent Management: A Call-To-Action and Blueprint for Success,” Court Manager 25, no. 4 (2010): 36.

- Kevin J. Bowling, “Building Bench Strength©: Succession Planning Readiness,” paper, ICM Fellows Program, May 2011, p. 9.

- Relevant publications include Succession Planning: Preparing Your Court for the Future (First Judicial District of Pennsylvania, 2006), with David C. Lawrence; Succession Planning: Workforce Analysis, Talent Management, and Leadership Development (NACM Mini Guide, 2008), with Patricia Duggan, Janet Cornell, Suzanne Stinson, and Kelly McQueen; and Resource Guide: Establishing a Succession Planning/Talent Management Program (Hagatna, Guam: Judiciary of Guam, 2013), with Jacqueline Zahnen Cruz.

- In the context of TMPs, the word “competency” is more narrowly defined than is the case within the NACM Core®, where a competency encompasses both KSAs and personal characteristics contributing to proficiency.

- Id. at 9.

- Given that a TMP’s assessment requirements might exceed the time and skills of some courts, there is an opportunity for institutions like NCSC and for professional associations to identify personal characteristics and behaviors that are linked to achieving excellent performance in key positions.

- Erin Boettge, “How to Improve Learning Transfer and Retention,” eLearning Industry, March 27, 2017.

- The Core® Competency Achievement Program “Core Champion” proposal would establish a program to encourage greater exposure to the contents of the competencies while avoiding the logistical complexities of a true professional certification program. At this writing, program details are being developed, and there would be no immediate target timeline by which an individual would be expected to achieve the program goals.

- “While orientation might be necessary—paperwork and other routine tasks must be completed—onboarding is a comprehensive process involving management and other employees that can last up to 12 months.” Roy Maurer, “New Employee Onboarding Guide,” SHRM. “Overall, effective onboarding should acclimate the new employee to allow him or her to become a contributing member of the staff in the briefest period possible, while engaging the employee to enhance productivity and improve the opportunity for the company to retain the employee.” Sean Little, “What Is Employee Onboarding—and Why Do You Need It?” SHRM Blog, February 26, 2019.

- Katy Tynan, “3 Ways to Improve Learning Retention in Your Training Program,” Corporate Training, eLearning, Micro Learning, September 15, 2017.

- Boettge, supra note 19; Nikos Andriotis, “Make Your eLearning Stick: 8 Tips and Techniques for Learning Retention,” Talent LMS, April 24, 2017; and Brigg Patten, “6 Ways to Improve Learner Retention,” Training Industry, September 19, 2016.

- The recorded online version of ICM’s CCM courses already include video content, study assignments, writing projects that are evaluated by faculty, and unit quizzes that require a score of at least 70 percent to pass. According to Margaret Allen, ICM’s director of National Programs, ICM intends to make the future versions of these courses more interactive. The number of annual registrations for ICM’s online courses has been rising gradually, almost reaching 250 in 2019. (Telephone conversation with Margaret Allen on February 28, 2020.) In addition, since March 2020, ICM has rapidly developed live, remote versions of many of its national courses as a response to the pandemic.

- In 2019, the principals of Court Leader, https://courtleader.net/, and eDevLaw (now eDevLearn, https://edevlearn.com/) presented a project concept to the NACM Board for the development of online micro-courses based upon the Core®. Although the Board decided that NACM would not oversee such a project itself, NACM does welcome the development of such resources so long as the NACM Core® is properly attributed. As of December 2020, the eDevLearn team was nearing completion of a set of micro-courses covering the Workforce Management competency.