The ordinary administration of criminal and civil justice . . . contributes, more than any other circumstance, to impressing upon the minds of the people affection, esteem, and reverence towards the government.

Alexander Hamilton, Federalist No. 17, in Clinton Rossiter (ed.), The Federalist Papers (New York: New American Library, 1961), p. 120.

The strength of the judicial system rests largely on the trust and confidence the public, and other agencies, have in a system that fosters integrity, transparency, and accountability.

National Association for Court Management, The Core® in Practice: A Guide to Strengthen Court Professionals Through Application, Use, and Implementation (Williamsburg. VA: National Association for Court Management, 2015), p. 4.

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Hon. David A. Brock, Chief Justice, Supreme Court of New Hampshire

As Alexander Hamilton argued in The Federalist Papers, the day-to-day decisions of state and local judges, by embodying the rule of law, are fundamental for citizens to believe in the legitimacy of our form of government. More recently, the National Association for Court Management (NACM) has emphasized that court professionals in their day-to-day work must consistently demonstrate the integrity, transparency, and accountability of the judicial branch to sustain the ongoing trust and confidence of citizens and other government entities and promote the legitimacy of the courts.

In 2000 those premises were tested when New Hampshire experienced a constitutional crisis involving the impeachment of Chief Justice David Brock. Brock’s critics viewed him as hostile toward legislative prerogatives and irresponsible in his administration of the state judiciary. His supporters saw him as a target of legislators’ rage over unpopular court decisions. Both sides, however, agreed implicitly on one point. Institutionally, legislative-judicial relations had been coming undone for some time, despite what Chief Justice Brock was fond of saying: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”1

Impeachment proceedings against Brock reflected an emerging view among many legislators that there had been too many recent incidents in which there was an appearance of injustice in the courts. Those incidents were diminishing the perceived legitimacy of the courts in the eyes of some legislators and public-opinion leaders. And this led to the filing of impeachment charges seen necessary to preserve the perceived legitimacy not only of the judiciary, but also of the entire state government.

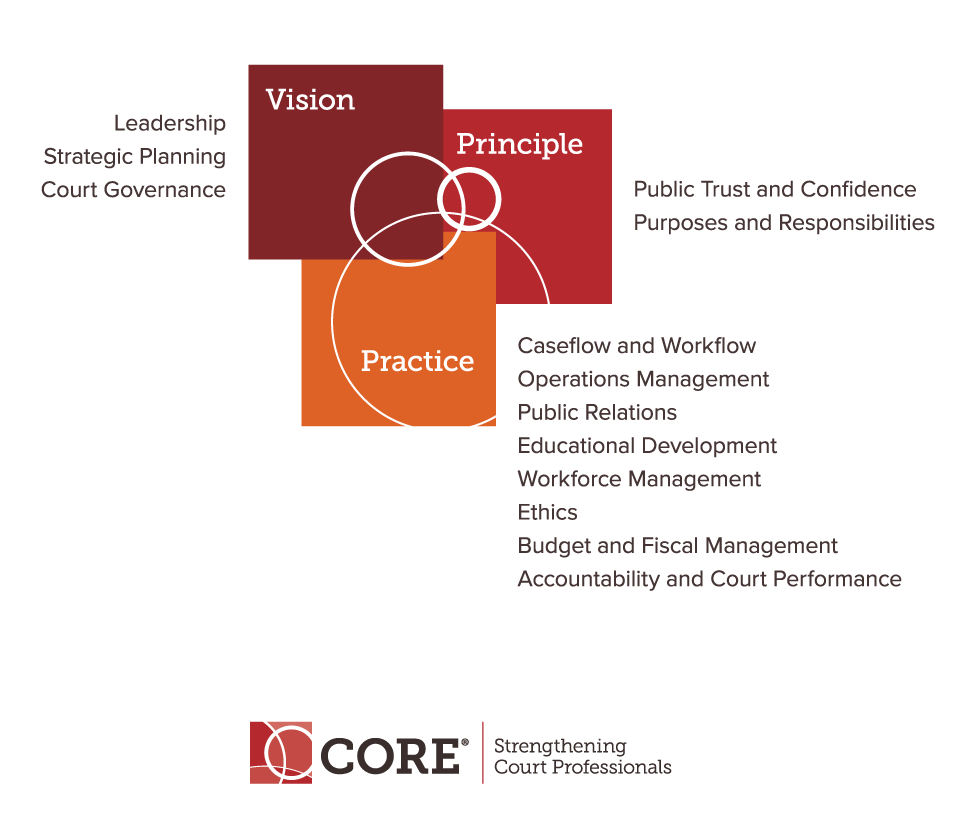

Nearly two decades after the crisis in New Hampshire, the history, proceedings, and aftermath of the Brock impeachment provide a case study in court governance and management for members of NACM. There are insights to be derived from it to aid the professional development and effectiveness of court professionals in keeping with the vision, principles, and practices that constitute the NACM Core® of what court professionals need to know.2 The Core essentials are illustrated in Figure 1.

Source: NACM “Core Essentials,” http://nacmcore.org/app/uploads/NACM-Pictoral-Final.png (as last viewed on March 17, 2018).

The Background in New Hampshire’s State Constitutional History

In 1784 New Hampshire voters ratified a constitution elevating the legislature over both executive and judicial organs of government. State constitutional provisions thus reflected the “populist” dimension of New Hampshire’s civic culture, the dominant strain at its founding and perhaps to this day.3

Citizens’ mistrust of entrenched power and the “elites” holding it had clear implications for the administration of justice in the state. The judiciary was formally subordinate to the legislature, which was granted full constitutional power to create and abolish all courts in the state.4 In the 19th century, the legislature exercised this power five times through “court clearances” involving abolition and reconstruction of the state’s highest court.5

New Hampshire’s approach to the selection and tenure of judges — appointment by governor and council for “good behavior” until age 70 — is uncommon. Starting before the Civil War, most states have made judgeships elected positions, primarily to strengthen judges’ powers against the other branches of government by granting them their own popular mandates. In New Hampshire that movement was resisted even as it crested elsewhere. Today, the state remains one of only three (with Massachusetts and Rhode Island) where judges are subject to neither partisan nor retention election, nor to reappointment by legislative or executive action.

But if the judiciary was initially configured as institutionally ancillary to the elected branches, judicial leaders worked from the beginning to establish the primacy of legally trained professionals over elected officials in the day-to-day administration of justice. Early in the 19th century, the highest court in the state held that legislative review of court decisions under a “redress of grievance” process was unconstitutional as a legislative usurpation of judicial powers, thereby confirming the power of judicial review under the state constitution. See Merrill v. Sherburne, 1 N.H. 199 (1818). This feature of New Hampshire’s judicial culture — vigilance against the intrusion of political agendas into the dispensation of justice — represented a counterpoint to the state’s well-attested civic populism.

The constant threat of “court clearances,” by means of which the legislature exercised its plenary power to abolish and reconstitute the highest court in the state, was always troubling. Although they were always a consequence of partisan political disputes, and never in retaliation for unpopular court decisions, they were understandably unsettling for the judiciary.

A turning point came about in 1901, when leaders of the two major parties decided that stabilization of the judiciary was really in each party’s interests, and that the tumult caused by the 19th-century court clearances should be avoided. The result was an informal “gentlemen’s agreement” regarding the composition of the state’s highest court and general-jurisdiction trial court. Each bench was to contain representatives of both parties, with the party in power retaining only a bare overall majority.6

The “gentlemen’s agreement” worked. From 1901 through 1966, there were no more court clearings. On the whole, New Hampshire’s judges and legislators achieved a kind of modus vivendi permitting the former to administer justice as they saw fit, so long as the latter could make the laws those courts applied without fear of serious judicial interference. It was the gradual erosion of this modus vivendi after the achievement of judicial modernization that set the stage for the impeachment crisis of 2000.

Judicial Modernization

The “judicial modernization” movement, initiated by Roscoe Pound in the early 20th century7 and carried forward by Arthur Vanderbilt in the middle of the century,8 had a significant impact in New Hampshire. The movement’s essential goal was enhancing the quality of state-level justice by fully “de-politicizing” judicial administration. Favored measures included the consolidation of courts into a single system under judicial supervision; judicial control of the state bar; and ethical codes written and enforced by legal professionals rather than elected officials. Such elements of judicial modernization were widely adopted in many states after World War II,9 and New Hampshire adopted them in the last third of the century.

Change began in 1966, when New Hampshire became the last state in the country to grant its high courts constitutional recognition through the ratification of Article 72-a in Part 2 of the New Hampshire Constitution. A unified court system was secured by statute in 1971. In 1978 voters approved another constitutional amendment that became Article 73-a, granting the chief justice of the supreme court administrative authority over the entire court system, to be financed by the state rather than by local governments. With these measures, New Hampshire’s citizenry granted their judiciary a level of institutional independence, and their judges a level of protection from political influence that they had never enjoyed before.

But even while state voters were “modernizing” their judiciary, they repeatedly and emphatically rejected efforts to similarly modernize the executive and legislative branches of their government. Across the nation, favored measures included expansion of governors’ powers and extensions of their terms of office; expansions of legislative staff and budgets; expansions of legislative sessions; and reductions in the size of lower chambers, accompanied by enlargements of upper chambers.10 But in New Hampshire, voters decided again and again that they did not want more “professionalized” politicians. There, such measures were seen as undemocratic attempts to replace the state’s honored citizen-legislators with a technocratic elite dangerously insulated from the vox populi.

Growing Legislative-Judicial Tensions

After constitutional and institutional changes in 1966-78 yielded a judiciary no longer subject to legislative power to create and abolish courts, legislative mistrust of courts may have been inevitable. Whether the crisis of 2000 was foreordained, however, is another question. Mistrust would harden into implacable antipathy only after a long series of conflicts, beginning with clashes over how, and by whom, judicial affairs were to be administered.

Historically, constitutional power to discipline and remove judges had been reserved to elected officials, via impeachment or bill of address.11 In the 1970s, however, the supreme court asserted authority to monitor judges’ behavior, if not to remove them, through both court rulings12 and the creation of a Judicial Conduct Committee (JCC).13 The JCC, accountable to the supreme court and enforcing its ethics code, represented a clear expansion of the court’s administrative authority. Yet legislators balked when the court asserted in State v. LaFrance, 124 N.H. 171, A 2d 340 (1983), that they must not intrude on what the justices considered exclusive judicial authority over courtroom procedures. LaFrance involved a statute authorizing a police officer to wear a firearm in court. The supreme court held that the statute violated separation of powers and was an unconstitutional infringement of a judge’s power over courtroom proceedings.

The next clash came in the 1990s over rules of evidence. The legislature, aiming to replicate changes in the federal rules of evidence, requested an advisory opinion from the supreme court on the constitutionality of a proposal to grant a “rebuttable presumption of admissibility” for evidence of previous similar crimes by defendants in sexual-assault cases. The justices responded that the proposed statute would violate separation of powers by restricting court discretion to determine the relevance of evidence. See Opinion of the Justices (Prior Sexual Assault Evidence [PSAE]), 141 N.H. 562, 688 A.2d 1006 (1997). Elected officials aware of the state’s history of legislative involvement in evidentiary questions were not the only critics of that opinion.14

Fears of a self-aggrandizing judiciary were clearly heightened in many legislators’ minds by the John Fairbanks scandal. A probate lawyer and part-time district court judge, Fairbanks fled the state after his indictment for theft in 1989, disappearing until his death in a Las Vegas hotel room four years later. What concerned legislators was not just Fairbanks’s own misdeeds, but the failure of the judicial branch’s internal ethical monitors to act on them despite longstanding complaints.15

Legislative investigators were particularly frustrated by the confidentiality protocols of the JCC, which precluded access to information investigators deemed necessary to determine the full scope of judicial corruption. See Petition of Burling, 139 N.H. 266, 651 A. 2d 940 (1994). Successive investigating committees were empaneled, one of which heard Chief Justice Brock himself attribute the problems to surviving traces of the premodern judicial regime (e.g., part-time judges and elected probate registers). Then-Governor Steve Merrill, however, provided an alternative interpretation, one more congenial to some legislators’ views. He argued that judicial modernization had gone too far, removing judges from the necessity of public accountability.16

It was in that atmosphere of deepening legislative concerns about the direction and integrity of the new-model judiciary that multiyear litigation about public-education funding burst upon the state. In a 1993 ruling, Claremont School District v. Governor, 138 N.H. 183, 635 A. 2d 1375 (1993) (Claremont I), Chief Justice Brock wrote for a unanimous court that Article 83 of the state constitution requires the state to provide free, universal education to all. Holding that all citizens have a substantive right to an adequate education, the court left the definition of “adequate” to the legislature. But in a subsequent 1997 decision, Claremont School District v. Governor, 142 N.H. 462, 703 A. 2d 1353 (1997) (Claremont II), the court held that financing elementary and secondary public education is a state and not a local obligation, and that allowing wide variations in property-tax support for education in different municipalities did not meet the requirement for “proportionate and reasonable” taxes under Part 2, Article 5 of the state constitution. Holding that education is a fundamental right warranting strict scrutiny, the court then ordered the state to determine appropriation levels sufficient to meet guidelines approved by the court for what is a constitutionally “adequate” education.

The court’s decision in Claremont II provoked a protracted constitutional battle, with multiple failures by the legislative and executive branches to meet constitutional requirements as defined by the supreme court, in large part because the state constitution, unlike that in any other state, does not authorize excise or income taxes. Instead, the elected branches of state government would have to fulfill the state’s obligations through state-level property taxes and other revenue sources.17 Critics of Claremont II maintain that it changed a dispute over education adequacy into one over taxes, calling it “a direct judicial challenge, clothed in constitutional garb, to the state’s culture of limited government, limited taxation, and local control.”18

The Constitutional Crisis

In addition to freeing the judiciary from subservience to legislative power to reconstitute courts, the constitutional and institutional changes adopted in 1966-78 may also have had dramatic unintended consequences for the partisan politics of judicial appointments, as one commentator has observed:

The “gentlemen’s agreement” regarding appointment to the courts from both political parties fell into disuse in the late 1970’s. It could be argued that the Supreme Court lost whatever political constituency it had, and that cutting the Court loose from a political mooring resulted in its being buffeted by political winds.19

Yet legislators retained the power to remove individual judges through impeachment or address. With judges no longer protected by the “gentlemen’s agreement,” they might be more vulnerable to the effects of “political winds” arising from legislators’ exercise of their removal power.

The first salvo came in January 1999, when a state representative and a state senator cosponsored a bill to have Brock removed by address.20 The bill criticized Brock, as head of the judiciary, for trying to silence attorney critics of court decisions, for concealing records of judicial misbehavior, for attempting to intimidate a legislator, for usurping authority of the other branches of government, and for “pro-active behavior in the realm of policy.”21 After it was referred to a joint committee composed of six representatives and six senators, however, the joint committee members voted unanimously against the bill for lack of specificity, after which the legislature decisively rejected it.22

Although the 1999 bill of address against Brock failed, it was nonetheless a highly significant step. Even if its charges lacked specificity, they were certainly rooted in a traditional vision of New Hampshire civic culture and democracy, in which all public officials must be tightly controlled and kept ever mindful that they are agents, not masters, of the people.23 For some time, that vision had been on a collision course with a newer one incorporating the fully independent judiciary that voters themselves had midwifed with the constitutional amendments of 1966 and 1978. Even though those amendments had been endorsed by voters, judicial modernization in the form of court unification, administrative autonomy, and various measures taken to fortify judicial independence nonetheless represented a departure from the state’s historic tradition of legislative supremacy. For legislators sharing that perspective, such events as the Fairbanks scandal, the Prior Sexual Assault Evidence advisory opinion, and the decisions in Claremont I and II were steps toward a catastrophe that had become inevitable from the moment voters had allowed their judiciary to slip the leash of popular, legislative control.

That catastrophe erupted in February 2000, when the supreme court had to hear the appeal from a trial court decision on the divorce of one of its members, Justice Stephen Thayer. All of the justices had to recuse themselves. In a conference of the justices, when Chief Justice Brock announced the names of the substitute judges that he had appointed to hear that case, Thayer objected vehemently to one of the replacement judges. Knowing that it was a violation of court procedures for one judge to discuss a case involving a colleague in the presence of the other judge and believing that this was not the first time that Thayer may have violated judicial ethics and perhaps even criminal statutes, Supreme Court Clerk Howard Zibel reported the matter in a memorandum to Attorney General Philip McLaughlin.

Learning in late March 2000 that he would be the target of a grand-jury investigation by the attorney general’s office, Thayer’s attorneys entered discussions with prosecutors, resulting in his resignation from the bench. Prosecutors subsequently presented no criminal charges against him to the grand jury.24 With the involvement of McLaughlin, however, Brock’s own fortunes took a sharp turn for the worse.

Among other things, the attorney general’s inquiry unearthed the fact that, for years, the court had allowed justices to comment on written opinions in cases from which they had been recused. Largely on that basis, McLaughlin urged legislators to conduct their own investigation of court practices, and the House Judiciary Committee (HJC) promptly accepted his suggestion, using the recent impeachment of President Bill Clinton as a blueprint.25 While the HJC concluded that Brock could not be held responsible for a recusal policy that predated him, they did find suggestions that he might have attempted to improperly influence a 1987 case involving the then-majority leader of the state senate. See Home Gas v. Strafford Fuels, 130 N.H. 74, 534 A. 2d 390 (1987). They also found indications of unethical ex parte conversations with Thayer, as well as possible concealment of relevant information from the attorney general. Finally, the HJC members concluded that Brock committed perjury while testifying before them.

After three months of investigation, the result was an overwhelming bipartisan vote by the full house of representatives in July 2000 to file four articles of impeachment against Brock in the senate, alleging that he:26

- Committed the impeachable offense of maladministration by telephoning a lower-court judge in 1987 to check the status of the “Home Gas” case involving a company owned by the then-state senate majority leader;

- Committed the impeachable offense of maladministration by engaging in ex parte discussions with Justice Thayer about the justices to be appointed to hear the appeal of Thayer’s divorce case;

- Lied under oath to the HJC, hindering its impeachment investigation by denying ex parte communications with Thayer and denying the “Home Gas” telephone call; and

- Committed the impeachable offense of maladministration by overseeing a practice allowing recused and disqualified justices to receive draft opinions and to attend case conferences, permitting them to comment on and influence decisions in those cases.

With the filing of those charges in the senate, Brock became only the second judge in New Hampshire history to be impeached.27 He was only the sixth state court chief justice in American history to face impeachment charges.28

Before trial began, the senate voted in August to require a two-thirds vote for conviction. Of the 24 senators, two disqualified themselves, so that 15 of the 22 sitting senators would be required for a guilty verdict. The impeachment trial was televised, and testimony began on September 18. On October 10, after three weeks of hearings, the senate voted to acquit Brock of all charges. Yet the impeachment was hardly without consequence, as developments in its aftermath would demonstrate.

Court Governance Efforts After the Impeachment

After Chief Justice Brock was acquitted, there was general agreement that changes were required in how the judiciary related to citizens and other branches of government. Starting in 2001, efforts to make such changes took different directions based on competing perceptions of what would be required.

A critical issue after the impeachment involved revision of judicial discipline practices to enhance their credibility with citizens and elected officials. In January 2001, a blue-ribbon task force created by the supreme court delivered a report recommending that compliance with the code of judicial ethics be mandatory, with failure to comply being a potential basis for disciplinary action. They urged the establishment of a new conduct commission independent of the court in terms of membership, physical location, staffing, and budget.30 In response, the supreme court entered an order creating that new conduct commission, as recommended by the task force, with the pre-task-force JCC remaining temporarily in existence to complete action on all pending matters until after legislative funding was available for the new commission. See N.H. Supreme Court Order (May 7, 2001).

The legislature had different expectations, however, and it established a conduct commission of its own by statute. See N.H. Senate Bill (SB) 197 (2001), enrolled as N.H. Laws 2001, Ch. 267, largely effective July 1, 2001. Then in 2003 it enacted another statute, requiring all complaints against judges and clerks under the 2001 statute be heard by the new statutory commission rather than the holdover JCC. See N.H. House Bill (HB) 4, enrolled as N.H. Laws 2003, Ch. 319:171, effective January 1, 2004. The JCC thereupon filed a court petition challenging the constitutionality of the 2003 statute. In June 2004, the supreme court ruled the statute unconstitutional, holding that the regulation of court proceedings and officers, including the power to discipline judges, is an inherent and exclusive power of the judicial branch. See Petition of Judicial Conduct Committee, 151 N.H. 123, 855 A. 2d 535 (2004). With the acquiescence of the legislature, the court then took steps to resolve the issue by following task force recommendations and creating a new JCC, with membership including executive and legislative appointees, formal independence from the supreme court, and its own separate office location, staff, and budget. See N.H. Supreme Court Order, R-2004-004 (January 25, 2005).

Another critical issue after the impeachment was the proper role of the legislature in promulgating court rules of practice and procedure. Influential commentators disagreed with the justices’ assertion, in their 1997 advisory opinion on prior sexual assault evidence, that the judiciary had exclusive constitutional authority over court rules under Part 2, Article 73-a of the New Hampshire Constitution.31 But in 2002, 2004, and again in 2012, proposals to amend Article 73-a, giving the legislature concurrent power to enact statutes that would prevail over court rules in the event of a conflict, failed as ballot questions to gain voter approval. See N.H. General Court, Constitutional Amendment Concurrent Resolution (CACR) 5 (2002), CACR 5 (2004), and CACR 26 (2012).

It is significant that supreme court representatives had expressed support for CACR 26 in legislative hearings. As a result, and despite the failure of CACR 26 as a ballot question, the court held in a unanimous decision that the legislature shares legitimate constitutional authority with the judiciary to regulate court procedure, except that any procedural statutes must not compromise core adjudicatory functions or violate the constitutional rights of persons in court. See Petition of Southern N. H. Medical Center, 164 N.H. 319, 55 A.3d 988 (2012).

Yet another set of efforts after the Brock impeachment had to do with adopting newer 20th-century mechanisms for ensuring judicial accountability. Such efforts, involving the elected branches of government while retaining the institutional independence gained for the judicial branch in 1966, appear to have been successful.32

To bring greater rigor to judicial selection, the idea of a judicial selection commission, applying specified merit criteria in the consideration of judicial nominees, has been introduced. This approach was first used in 1940 in Missouri, and today it is widely recognized as a viable alternative to the election or appointment of judges without merit screening.33 The idea was first implemented successfully in New Hampshire by Governor Jeanne Shaheen, who issued an executive order creating a judicial nominating commission just before the vote to impeach Brock (Exec. Order 2000-9 [June 30, 2000]). Yet efforts by statute or constitutional amendment to make merit selection permanent have been unsuccessful. Judicial merit selection has survived, but only through gubernatorial orders. With the exception of Governor Craig Benson, every subsequent governor through current Governor Christopher T. Sununu has appointed and relied upon recommendations from a judicial selection commission (Exec. Order 2017-01 [February 6, 2017]).

Also promoting judicial accountability while retaining institutional independence is the notion of regular and programmatic judicial performance evaluation. The New Hampshire Supreme Court introduced a performance evaluation program in 1987, patterned on American Bar Association guidelines.34 One legislator, however, observed that the operation of that evaluation program was “sporadic at best.”35 In April 2000, legislation was enacted for the judiciary to design and implement a new program for regular performance of all trial judges, and the supreme court adopted a new rule that directly followed the statutory language. In March 2001, it formally established a comprehensive performance evaluation program for all trial and appellate judges, as well as marital masters (quasi-judicial officers hearing family matters), with further subsequent refinements through legislative-judicial collaboration.36

Lessons for Court Professionals

From time to time, in meetings to discuss possible court management changes recommended by representatives of the National Center for State Courts, Chief Justice Brock would say, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” For judges and court managers, the significance of Brock’s impeachment in 2000 is that it was all about perceptions of judicial integrity, transparency, and accountability. The lessons that court professionals can derive from the historical background, trial proceedings, and aftermath of the constitutional crisis the impeachment represented can fruitfully be considered in terms of how its specific details relate to the “core essentials” for effective performance by court professionals (see Figure 1).

On matters that might affect public perceptions of judicial integrity, transparency, and accountability, however, it is critical that court professionals be sensitive both strategically and in their day-to-day practices to “notice and question things that had previously been taken for granted.”37 The first article of impeachment against Brock, alleging that he intervened by calling the trial judge about delays in a case involving an influential politician, might not have raised eyebrows before the judicial modernization of 1966-78 and the adoption of a judicial ethics code with mandatory provisions. But in 2000, when legislators in an impeachment investigation considered that episode in retrospect, it had the appearance of impropriety. Today’s court professionals might prefer that such a politically charged matter be treated with full documentation within the framework of established procedures for monitoring timely completion of judge rulings on matters under advisement.

The remaining articles of impeachment against Brock arose in large part from the February 2000 discussion by the supreme court justices in conference, with Justice Thayer present and participating, about the appointment of replacement judges to hear the appeal in Thayer’s own divorce case. The participation of a justice in the consideration of appeal cases from which they were recused was a practice that predated Chief Justice Brock’s tenure on the court, and it was a topic that had previously received little or no attention in the national professional literature on the ethics of judicial disqualification and recusal.38 It had long been taken for granted in the private deliberations of the justices in New Hampshire; however, it presented the obvious appearance of impropriety when the attorney general and legislators learned of Thayer’s ex parte involvement in the appellate review of his own divorce case.

Beyond the immediate events providing proximate cause for Brock’s impeachment, there is much to be learned from what happened before and after that crisis. In the complex environment of court governance, one can say that effective court leaders must constantly be ready to make adaptive changes and corrections in response to unexpected developments and the unexpected consequences of their judicial and administrative activities and decisions. While they should be vigilant in the protection of judicial independence, events in New Hampshire support the proposition that effective court professionals must ensure accountability in terms of performance meeting established public standards.39 Thus, the following “before-and-after-impeachment” narrative can be offered:

- After the 1966-78 constitutional amendments, the integrity, transparency, and accountability of the New Hampshire judiciary were cast in serious doubt by the Fairbanks and Thayer scandals. In the wake of the Brock impeachment, judicial ethics and the organizational means for judicial discipline were revised to enhance transparency and limit the appearance of judicial impropriety.

- To permit appropriate attention to judicial behavior before it might reach a stage warranting disciplinary measures, the judiciary worked with the legislature to develop routine methods for evaluating judicial performance at all court levels.

- Although the state continues its historical tradition of rejecting judicial selection and retention by popular election, judicial appointments by governor and council since 2000 have largely been undertaken through a merit selection process with the aid of a gubernatorially appointed judicial selection commission.

- Perhaps the most contentious sources of legislative-judicial tension after 1978 had to do with the extent to which authority to prescribe court rules of practice, procedure, and administration was vested exclusively in the judiciary, as the supreme court asserted in its advisory opinion on the constitutionality of a proposed statute relating to prior sexual-assault evidence in criminal prosecutions. See Opinion of the Justices (Prior Sexual Assault Evidence [PSAE]), 141 N.H. 562, 688 A.2d 1006 (1997). Reflecting a view among many legislators, and even members of the legal profession, the supreme court in a 2012 decision held that the legislature had a legitimate role in the promulgation of court rules, as long as legislative actions met constitutional requirements. See Petition of Southern N. H. Medical Center, 164 N.H. 319, 55 A.3d 988 (2012).

Conclusion

As part of putting the NACM Core® into practice, effective court professionals must understand the need to focus “on the importance of an open and transparent system to promote public trust and confidence and the collective interest of court leaders to increase the public’s understanding of the courts.”40 As painful an experience as New Hampshire’s impeachment trial may have been for Chief Justice Brock and others, it has led to the development of means for more credible assurance of judicial accountability in an institutionally independent court system. Court professionals should understand that this must always be viewed as a “work in progress.” We should actively participate in ongoing efforts with citizens, lawyers, and government officials in other branches to ensure the rule of law by promoting public trust and confidence in our states’ judicial institutions.

About the Author

David C. Steelman is a retired member of the Massachusetts and New Hampshire bars. From 1974 through 2013, he worked for the National Center for State Courts as an attorney, regional vice president, and principal consultant. He was the lead author of Caseflow Management: The Heart of Court Management in the New Millennium (2000, 2004), and a coauthor (with Richard Van Duizend and Lee Suskin) of Model Time Standards for State Trial Courts (2011). He also contributed to NACM’s 2015 revision of the Core® — a roadmap for what court professionals need to know and effectively be able to do to promote excellence in the administration of justice.

Notes

- Chief Justice David A. Brock was a graduate of Dartmouth College and the University of Michigan Law School, a Marine captain, a lawyer in private practice, and a United States attorney before he became a judge. The phrase “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” is said to have been popularized by Georgia native Bert Lance in 1977, while he served as director of the Office of Management and Budget for President Jimmy Carter. Jason Perlow, “’If It Ain’t Broke Don’t Fix It’? Bad Advice Can Break Your Business,” ZDNet, April 8, 2014.

- See NACM, “Core Essentials: What Court Professionals Need to Know,” Core website, 2018.

- In New Hampshire: An Epitome of Popular Government (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1904), Frank B. Sanborn recounts the development of local self-government and freehold land tenure by New Hampshire colonists’ rejecting property and trade monopolies sought by royal grantees under which most people would hold land not as owners, but only as tenants.

- Until its amendment in 1966, the language of N.H. Const. Part 2, Article 4 provided that no court (even the highest court) was structurally independent from legislative power. Article 4 was copied from Part 2, Article 3 of the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution. Unlike New Hampshire, however, the prior existence of a court of last resort in Massachusetts, called the Supreme Judicial Court in the 1780 constitution, was consistently understood to mean that the highest court in that state had constitutional status independent of any legislative power to create or abolish courts. See Walton Lunch Co. v. Kearney, 128 N.E. 429, 432 (Mass. 1920).

- At different times in the 19th century, the highest court of New Hampshire was called the “Superior Court of Judicature” (1776-1813, 1816-1855, and 1874-1876), the “Supreme Judicial Court” (1813-1816 and 1855-1874), and finally the “Supreme Court” (1876-present). Charles G. Douglas III and Jay Surdukowski, “The New Hampshire Supreme Court: A History of Change,” New Hampshire Bar Journal 51 (2010): 10, 13. See also, Richard McNamara, “The Separation of Powers Principle and the Role of the Courts in New Hampshire,” New Hampshire Bar Journal 42 (2001): 66; Richard Upton, “The Independence of the Judiciary in New Hampshire,” New Hampshire Bar Journal 39 (1998): 56; and Charles R. Corning, “The Highest Courts of Law in New Hampshire — Colonial, Provincial, and State,” in Horace Fuller (ed.), The Green Bag: A Useless but Entertaining Magazine for Lawyers 2 (1890): 469.

- Upton, p. 59; and McNamara, pp. 71, 77, ibid.

- In addition to his famous presentation “The Causes of Popular Dissatisfaction with the Administration of Justice,” 29 Annual Report of the American Bar Association (1906): 395, see Pound’s Organization of Courts (Boston: Little, Brown, 1940).

- See Arthur Vanderbilt, Minimum Standards of Judicial Administration (New York: New York University Press, 1949), and The Doctrine of the Separation of Powers and Its Present-Day Significance (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1953).

- See Robert W. Tobin, Creating the Judicial Branch: The Unfinished Reform (Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts, 1999).

- See Jon Teaford, The Rise of the States: Evolution of American State Government (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2002).

- See N.H. Const. Part 2, Articles 17 (power of House of Representatives to bring articles of impeachment), 38 (Senate to hold impeachment trials), and 73 (judge tenure and removal by address).

- See, for example, In re Mussman, 113 N.H. 54, 302 A. 2d 822 (1973), where the question at issue was whether the supreme court itself had the power to investigate and, if necessary, discipline a district court judge, short of actual removal from office, but also raising the broader question of whether the constitutional power of the legislative and executive branches over judicial personnel excluded the judicial branch from policing its own ranks.

- The New Hampshire Supreme Court adopted a code of conduct based on the American Bar Association’s Model Code of 1972, and its 11-member JCC was created in 1977 to enforce it. The JCC in its original form was essentially an agency of the court, which appointed nine of its members and wrote the rules by which the committee functioned.

- Notable among the critics of the PSAE opinion was Robert J. Lynn, who at the time of Brock’s impeachment was a general-jurisdiction trial judge. See Lynn, “Judicial Rule-Making and the Separation of Powers in New Hampshire: The Need for Constitutional Reform,” New Hampshire Bar Journal 42 (2001): 44.

- The story of misconduct by Fairbanks and his flight from the law generated considerable public interest. See Royal Ford, “Scandalous Judge’s Legacy Won’t Die: Rural N.H. Town Reels from Tale of Disorder in the Court,” Boston Globe, September 18, 1997, B1. See also, Paul Montgomery, “Small-Town Scandal Still Casts a Long, Dark Shadow,” New Hampshire Magazine (July 1999): 8-13.

- Chief Justice Brock and Gov. Merrill expressed their views in a meeting of the legislative committee on November 12, 1996. See N.H. General Court, House of Representatives, “Synopsis of Committee Meetings,” 13-14, in “Report of the House Committee to Study the State Investigation of the John C. Fairbanks Matter,” January 1997.

- See N.H. Const. Part 2, Article 5. Regarding the implications of that article, see Marcus Hurn, “State Constitutional Limits on New Hampshire’s Taxing Power,” Pierce Law Review 7 (2009): 252. Hurn notes, “Despite one significant constitutional amendment and considerable evolution in judicial interpretation, it is still the case that true taxes must be on polls or property. New Hampshire remains unique among the states in denying the legislature the power to levy excise taxes as such” (pp. 253-54). Rather, the state has had recourse to such non-tax levies as fees, penalties, and special-benefit assessments.

- John M. Lewis and Stephen E. Borofsky, “Claremont I and II — Were They Rightly Decided, and Where Have They Left Us?” University of New Hampshire Law Review 14 (2015): 1, 12-13. Twenty years after the decision in Claremont II, the goals set in that decision may still be unmet for property-poor school districts. See Steve Norton and Greg Bird, “Education Finance in New Hampshire — Headed to a Rural Crisis?,” paper, New Hampshire Center for Public Policy Studies, Concord, 2017; and Lola Duffort, “Some Say N.H.’s School Funding Formula Could Lead to a Lawsuit,” Concord Monitor, March 5, 2018.

- McNamara, supra n. 5, p. 77.

- The New Hampshire Constitution’s provision on judicial tenure and removal by address provides that judges hold their offices during “good behavior” until age 70, and that the governor may remove a judge from office on a request by both chambers of the legislature on grounds warranting removal but insufficient for impeachment. N.H. Const. Part 2, Article 73.

- N.H. House Journal 18, 1999 Session (January 28, 1999), 272, House Address (HA) 1 bill text as introduced.

- N.H. House Journal 77, 1999 Session (July 1, 1999), 2070-72, HA 1 vote on committee report.

- On differing views of an elected representative in a democracy, see Hanna F. Pitkin, The Concept of Representation (Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles, 1967). For an analysis of notions of democratic representation during the time of the American Revolution, see John Phillip Reid, The Concept of Representation in the Age of the American Revolution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989).

- See Philip McLaughlin. Report of the Attorney General: in re: W. Stephen Thayer, III and Related Matters (Concord, NH: Office of the Attorney General, 2000), p. 21.

- See Elizabeth Mehren, “’Old-Boy’ System Causes Chaos on N.H. High Court. Law: Handling of Justice’s Divorce Places His and His Colleagues’ Actions Under Investigation,” Los Angeles Times, May 2, 2000.

- N.H. House Journal 56, 2000 Session (July 12, 2000), 1667-1719 and 1755, House Resolution 51 bill text as amended.

- In 1790 Justice Woodbury Langdon of the Superior Court of Judicature (then the state’s highest court) was accused of maladministration for “corruptly and willfully” neglecting his duty by refusing to hold court in three counties at appointed times. After articles of impeachment were filed, the senate trial was postponed, and Langdon resigned his position before trial began. See Nathaniel Bouton et al., Early State Papers of New Hampshire, vol. 22 (Concord, NH: Ira C. Evans, 1893), pp. 747-56.

- Before David Brock in 2000, the only state court chief justices in American history who had articles of impeachment filed against them were Edward Shippen (Pennsylvania, 1803); John McClure (Arkansas, 1871 and 1874); David Furches (North Carolina, 1901); Frederick Branson (Oklahoma, 1927); and Charles Mason (Oklahoma, 1929).

- For a day-to-day description of the impeachment trial by one of the participating senators, see Mary Brown, The Impeachment Trial of the New Hampshire Supreme Court Chief Justice (Pittsfield, NH: Lynxfield Publishing, 2001). For analysis of the development of the articles of impeachment, of critical pretrial decisions, and of the impeachment trial in the context of impeachment background and aftermath, see John Cerullo and David C. Steelman, The Impeachment of Chief Justice David Brock: Judicial Independence and Civic Populism (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017), chap. 7 and 8.

- Jonathan DeFelice and Wilfred Sanders, “Task Force for the Renewal of Judicial Conduct Procedures: Report to Supreme Court of New Hampshire,” Concord, 2001.

- See, for example, Lynn, supra n. 14. In 2010, Lynn became an associate justice of the Supreme Court, and in 2018 he became the chief justice. See also, Henry P. Mock, “Concurrent Resolution 5, the Linchpin of Judicial Reform,” New Hampshire Bar Journal 42 (2001): 23. As chair of the House Judiciary Committee in 2000, Rep. Mock led the impeachment investigation of Chief Justice Brock.

- For more details, see David C. Steelman and John Cerullo, “Judicial Accountability in a Time of Tumult: New Hampshire’s Impeachment Crisis of 2000,” Rutgers University Law Review 69 (2017): 1357.

- See Ryan J. Owens, Alexander Tahk, Patrick C. Wohlfarth, and Amanda C. Bryan, “Nominating Commissions, Judicial Retention, and Forward-Looking Behavior on State Supreme Courts: An Empirical Examination of Selection and Retention Methods,” State Politics and Policy Quarterly 15 (2015): 22.

- See University of Denver, Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, “Judicial Performance Evaluation: New Hampshire.”

- See Senate Judiciary Committee, Hearing on HB 568, Rep. Henry Mock testimony, N.H. Senate Calendar 17 (March 22, 2000), 28.

- See Senate Judiciary Committee, Hearing on SB 249, Atty. Howard Zibel testimony, N.H. Senate Calendar 3 (January 21, 2014).

- Karl Weick, as quoted in Mary Campbell McQueen, “Governance: The Final Frontier,” paper presented at the Harvard Executive Session for State Court Leaders in the 21st Century, Cambridge, Massachusetts, June 2013, p. 2.

- See Richard Flamm, Judicial Disqualification: Recusal and Disqualification of Judges, 2nd ed. (Berkeley, CA: Banks and Jordan, 2007, with updates through 2015).

- Mary McQueen writes the following in “Governance: The Final Frontier,” supra n. 37, at 3-4: “Accountability and autonomy are competing values . . . and, as such, potential sources of tension. . . . [T]he accountability movement represents an opportunity for leaders at the state or institutional level (for example, a local court) to craft different approaches to governance. Rather than trying to ‘beat back’ accountability efforts, leaders can take the opportunity to proactively define terms of accountability for fiscal matters and performance that preserve independence.”

- Paul DeLosh et al., The Core® in Practice: A Guide to Strengthen Court Professionals through Application, Use, and Implementation (Williamsburg, VA: National Association for Court Management), p. 5.

* This article is based on research done for the book, The Impeachment of Chief Justice David Brock: Judicial Independence and Civic Populism (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017), by John Cerullo and David C. Steelman. The author is deeply grateful to Professor Cerullo for his contributions to the quality of this article.