Today, Deena Davis is a certified peer support specialist who works in the same treatment court that saved her life and reunited her family.

Deena grew up in small-town Georgia, where she was an honor-roll student and captain of the cheerleading team. In sixth grade, her parents sat her down with her siblings and announced that they were getting divorced. With the trauma of the divorce, alcohol use disorder entered her family, and the comfort and safety of her once idyllic childhood crumbled. Deena went through high school masking any indication of the trauma at home while experimenting with substances to numb her pain. When she was 21, her boyfriend introduced her to methamphetamine. “I knew the second I did it that I was in trouble,” she recalls.

In the years that followed, substance use became a substance use disorder, and she cycled in and out of jail. She gave birth to two daughters; each time, she fought hard to protect them and resist using. But eventually, she found herself facing a judge and the very real possibility that she would be incarcerated and lose custody of her children forever. And that may have happened had it not been for a treatment court in Douglas County, Georgia. Rather than face traditional sentencing with little possibility of treatment or reunification, Deena was admitted into family treatment court, where recovery and regaining custody were the goals.

Describing her first encounter with the treatment court team, Deena says, “It was within the first five seconds, the way they looked at me, the way they treated me, the way they talked to me, that I realized if I could just believe them, my whole life could be different. I felt like a human being for the first time in probably 10 years.”

The Douglas County Family Treatment Court is one of 4,000 treatment courts nationwide, serving approximately 150,000 people a year. Treatment courts are among the most successful justice innovations for people with substance use and mental health disorders in our nation’s history. They save lives, reunite families, improve public safety, and save money. Nonetheless, treatment courts serve less than 10 percent of court-involved individuals with substance use disorders. The question, then, is how can the model be used to serve all those in need?

The Rise of Treatment Courts

In the late 1980s, Miami-Dade County, Florida was inundated with cases involving individuals suffering from substance use disorders. Courts and jails were overwhelmed, and everyone involved in the system was frustrated by the ongoing pattern of drug use, crime, and jail—the “revolving door” of the justice system. The same individuals would cycle in and out of the justice system without receiving treatment, only to reoffend and start the process over again.

Miami’s experience was not unique. Courts across the country were on the brink of collapse from the sheer volume of drug-related cases. But Miami found a new solution. Under the leadership of the state’s attorney, judiciary, and court administration, planning began for a new type of court docket designed to address substance use disorders while holding individuals accountable. If their new approach worked, it had the potential to reduce reoffending, caseloads, and jail populations while also saving money system-wide.

In 1989 Miami-Dade County launched the first drug court in the United States. It was a revolutionary concept. The program relied on a team approach—the judge, prosecutor, and defense counsel worked together with treatment providers, case managers, probation officers, and law enforcement in a nonadversarial, collaborative manner. Program participants received individualized treatment and other services while being closely monitored through regular court hearings, community supervision, and frequent drug testing. By combining treatment and ongoing monitoring, the drug court gave participants the support and structure they needed to succeed. In less than a year, they were seeing promise with this new approach.

It did not take long for other jurisdictions to follow when they learned about the impact Miami was having. As drug courts—now known as treatment courts—began to spread, a few things became apparent. First, the model would need to be defined and rigorously studied to see whether it would be successful. Training would be necessary to assist with the planning and implementation of new programs. And someone would need to lead and guide this movement on a national level. All Rise was founded in 1994 as the National Association of Drug Court Professionals to provide training, membership, and advocacy and has been at the forefront of the movement for justice innovation for more than three decades.

By the early 2000s, studies showed clear and convincing evidence that treatment courts work. The National Institute of Justice Multi-Site Drug Court Evaluation, the largest and most comprehensive study to date, found significant reductions in drug use and criminal behavior, as well as robust cost savings. Specifically, when measured against comparison groups, the study confirmed:

- 13 percent reduction in new crimes committed

- 20 precent reduction in return to drug use

- Cost savings of approximately $6,000 per individual served

What’s more, studies showed that they were going beyond treatment to help participants build lifelong skills to sustain their recovery. The study demonstrated improvements in education, employment, housing, and financial stability, along with reduced family conflict.

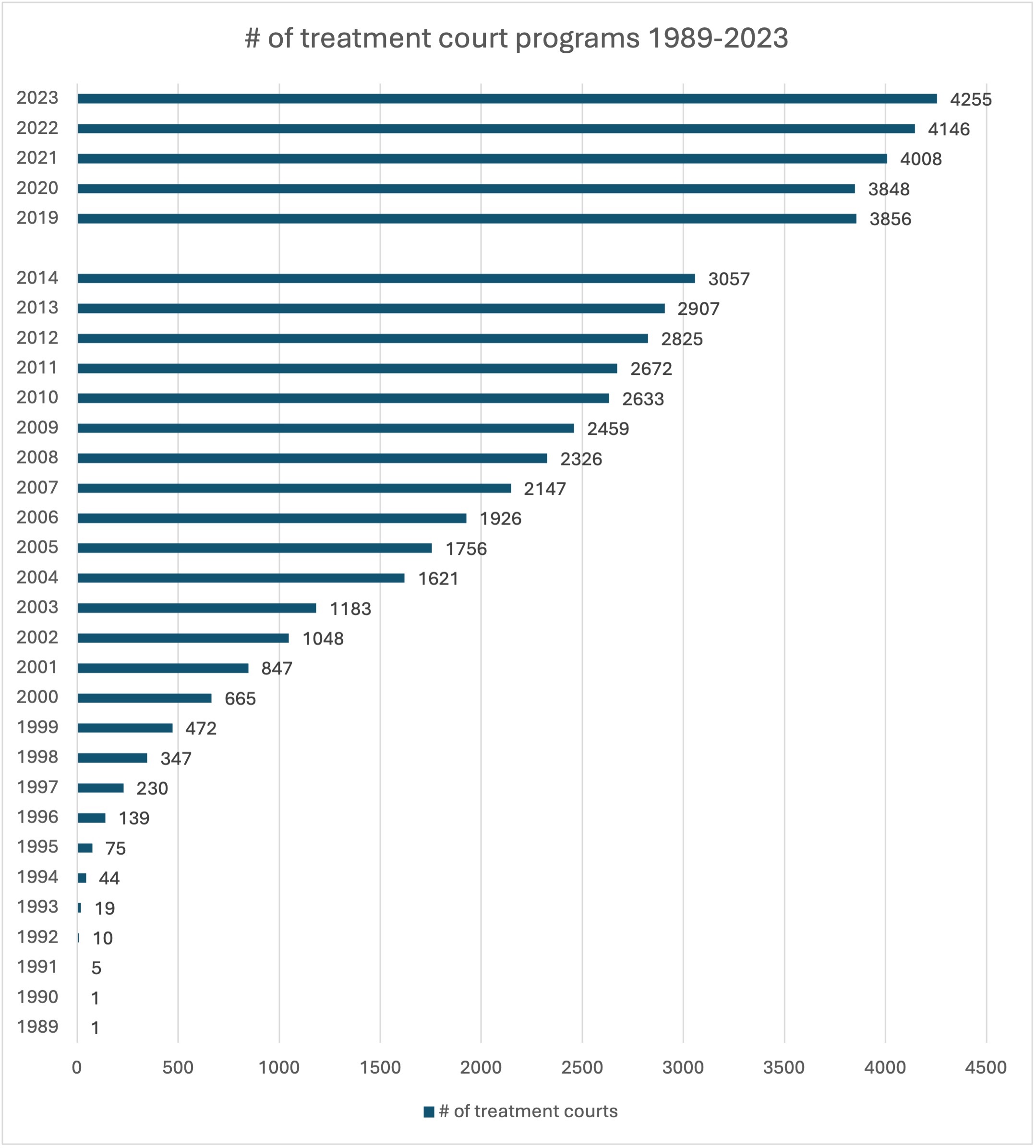

Treatment Court Growth Chart

Over the last two decades, the treatment court model has expanded rapidly across the country. The model has also diversified; there are impaired driving, juvenile, family, and veterans treatment courts, as well as tribal healing to wellness courts, mental health courts, and more. All Rise now works beyond the treatment court model to help implement evidence-based strategies and promising innovations across the legal spectrum, from first contact with law enforcement to corrections and reentry.

Many courtrooms in the country see individuals with substance use and mental health needs; All Rise now helps court professionals of all backgrounds and roles improve outcomes by addressing these issues at every intercept point.

Setting the Standard

With a growing body of research confirming that treatment courts work, researchers began investigating the model to answer key questions: Why do they work? Which elements of the treatment court model are most effective? Whom should treatment courts be serving, and how should courts respond to their behavior? In response, All Rise convened a committee of experts to meticulously review the vast scientific research on best practices in treatment courts, other correctional rehabilitation programs, and substance use, mental health, and trauma treatment. The committee distilled that vast literature into practical and measurable guidance for treatment courts and produced the Adult Treatment Court Best Practice Standards. The second edition of the standards is in production, with eight of the ten standards available now; the final two standards will be published by the end of this year.

It’s important to point out that the standards have held up to more than a decade of scrutiny. No provision from the first edition has been retracted or found erroneous in subsequent studies. In addition, they have helped to spawn the development of supplemental standards for specific treatment court models, including juvenile treatment courts and family treatment courts.

Application Beyond Treatment Courts

Treatment courts have proven to be highly effective at improving outcomes in criminal court, family court, and juvenile court cases involving individuals with substance use and mental health disorders. However, treatment courts are designed to work with a specific subset of the population—individuals at high risk of reoffending and with significant treatment needs—and they reach less than 10 percent of court-involved individuals in need of treatment. Broader solutions are needed to meet the scale of the problem. Fortunately, courts do not necessarily have to set up more specialized treatment court dockets to identify and address individuals with underlying substance use and mental health issues. Many of the evidence-based practices set forth in the Adult Treatment Court Best Practice Standards can be applied in regular court parts and at other stages of the justice system.

Here are three examples to consider.

All Rise’s Center for Advancing Justice is working to help courts implement universal screening, assessment, and referral to identify each person’s individual needs and route them to appropriate services and supports. (standards 1, 4, and 5).

1. Screening, Assessment, and Referral

No program works for everyone. As the standards make clear, effective justice system responses must be tailored to each person’s criminogenic risk and needs. High-risk individuals—that is, those at high risk of reoffending—should be more closely supervised in the community. High-need individuals should receive more intensive services targeted to meet their specific criminogenic needs, like treatment, housing assistance, and cognitive behavioral interventions. However, justice system actors typically do not have this kind of information when making decisions about cases.

All Rise helps jurisdictions adopt validated risk/need screening tools that identify a person’s criminogenic risk level and their specific areas of need.

Criminogenic Risk

An individual’s risk of being arrested for or convicted of any new crime or returned to custody for a technical violation.

Criminogenic Need

Risk factors for criminal recidivism that are potentially changeable or treatable (e.g., substance use, peer groups, lack of problem-solving skills).

If the risk/need screening indicates that an individual has a substance use issue, they can be referred to a qualified treatment professional for an in-depth clinical assessment to determine:

- If there is a substance use disorder

- The severity of the disorder

- The appropriate level of care

- Other factors like mental health and trauma issues

Judges and attorneys can then use this information to structure plea agreements, refer people to appropriate diversion programs, and connect people with targeted services and the necessary amount of supervision to promote positive case outcomes.

2. Treatment

When serving a population impacted by substance use and mental health disorders, understanding treatment is key, and the standards provide ample guidance that courts of all types can use to improve treatment outcomes for these individuals (standard 5).

First and foremost, research makes clear that only clinically trained professionals should perform assessments and make recommendations for establishing or adjusting treatment plans. In addition, treatment plans will also be more successful if they are:

- Evidence-based, including using medication for substance use disorders as prescribed

- Person-centered and developed in collaboration with the justice-involved client (e.g., setting goals and choosing from available treatment options)

- Based on a therapeutic alliance, where the client and treatment provider are mutually trusting and engaged in the work of therapy

- Designed in concert with recovery management services for long-term support beyond short-term interventions

- Integrated with mental health treatment services if the risk/need screening tool identifies co-occurring disorders

3. Equitable Justice

The standards contain a wealth of information for ensuring a more equitable justice system overall, demonstrating that evidence-based strategies can improve public health and public safety outcomes at every stage and setting of the legal process:

- Incorporating trauma-informed and gender-responsive practices (standard 5)

- Monitoring and rectifying racial, ethnic, and other sociodemographic disparities (standards 2 and 10)

- Providing culturally proficient services (standards 5, 6, and 8)

- Eliminating burdensome and unwarranted fines, fees, and costs (standards 1, 2, and 4)

- Accelerating access to treatment and medications for substance use disorder to reduce overdose and mortality rates (standards 8 and 10)

Where We Go from Here

Court managers can play a critical role in expanding programs and practices that improve outcomes for justice-involved individuals impacted by substance use and mental health. Whether your jurisdiction already has treatment court programs and would like to see better results, is interested in starting a treatment court program or specialty docket for the first time, wants to learn about how to incorporate evidence-based strategies to improve current operations and outcomes, or desires to innovate beyond these programs, All Rise stands ready to go on a journey with you. Our staff and faculty have wide-ranging expertise and experience to help you lay the groundwork and implement strategies at every intercept point.

We offer robust in-person and virtual opportunities. We also offer hundreds of free resources, searchable by your role, court type, and topic. From publications to webinars, case law to toolkits, podcasts to sample documents, as well as our e-learning center with self-paced online courses, it’s all right at your fingertips.

Each year, we convene more than 7,000 justice, treatment, and social service professionals for RISE, our annual conference that offers continuing education credit, unparalleled networking and connection, and a source of inspiration and motivation. RISE25 will be held May 28-31, 2025, at the Gaylord Palms Resort and Convention Center in Kissimmee, Florida. We would love to see you there!

Want to learn more? Sign up to receive our emails, and connect with us on Instagram, Facebook, or LinkedIn.

We see the hard and often lifesaving work you do in the court system every single day. We are grateful for your dedication, public service, and commitment to true justice. From all of us at All Rise, thank you.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Brooke Glisson is the associate director of communications for All Rise, the training, membership, and advocacy organization for justice system innovation addressing substance use and mental health at every intercept point. In this role, she helps develop and execute strategic internal and external communications, including serving as the managing editor for the All Rise Magazine, peer-reviewed Journal for Advancing Justice, and numerous other publications and products. An experienced writer, editor, project manager, digital content creator, and social media director, she has a critical eye for superior content, design, and audience engagement.

Chris Deutsch is director of communications for All Rise, the training, membership, and advocacy organization for justice system innovation addressing substance use and mental health at every intercept point. In this role, he oversees the development and implementation of all strategic internal and external communications, including crisis communication, brand alignment, messaging, web, traditional and social media, and marketing. He serves as the primary media contact and spokesperson for All Rise.