All courts are candidates for higher performance, and the High Performance Court Framework (HPCF, or the “Framework”) advocates concepts and processes by which any court can improve. In our two previous articles, we contended that the continuing difficulties that so many courts have with improvement is less a matter of unfamiliarity with what constitutes high performance than of not knowing how to achieve it. We have reviewed the concepts of the Framework and described our experiences with a variety of courts that have successfully employed those concepts to improve performance. The Framework is not a one-size-fits-all approach to court improvement, nor does it make the mistake of advocating perfection at the expense of good or incrementally better performance. In this third and final article, we suggest a few approaches that courts can use to start their own improvement efforts employing concepts from the Framework.

Fundamentals for Successful Change Efforts

Although no two organizations will follow an identical path to improvement, there are common elements among successful efforts at organizational change:

- leadership—ongoing and distributed;

- continuity—of leadership and processes;

- sense of urgency or need;

- compelling vision;

- effective communication;

- involvement of stakeholders;

- resource allocation

- empowered staff; and

- follow-through or feedback mechanisms.1

In our experience, these elements are closely related. Having a coalition of high-level court leaders—composed of both judges and administrators and often assisted by external participants—is necessary to initiate and sustain improvement efforts. Where leadership is shared, there is greater likelihood of developing and effectively communicating a common vision to which staff and other stakeholders will commit and less likelihood that any single individual’s departure will undermine performance initiatives. Intergovernmental pressures or data that suggest a problem often provide the sense of urgency needed to start performance improvement efforts; meanwhile, a compelling vision of the higher-performing court helps to empower staff and sustain improvement over time. The court must manage a variety of resources—human, technological, structural, and informational—to respond effectively to performance challenges. Ongoing, cyclical processes for self-assessment and progress monitoring provide mechanisms for collecting and analyzing performance data, formulating responses, and evaluating results. The Framework provides guidance to courts in obtaining and applying these elements.

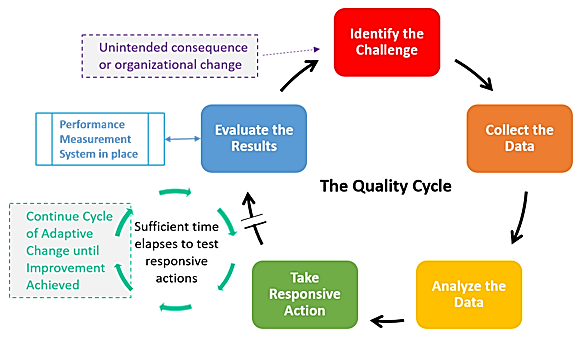

The four perspectives of the Framework—customer, internal operating, innovation, and social value—offer lenses through which a court can examine its operations before and while undertaking performance improvements. Combined with a court culture assessment, which is also recommended by the Framework, a court can use the perspectives to determine what aspects of its performance would be good targets for improvement efforts and which of the elements that are beneficial for change the court already has or needs to develop. The Framework’s Quality Cycle, like other change management and strategic planning approaches, suggests a cyclical series of steps by which a court can attempt improvement, building capacities for more significant performance improvement efforts over time.

The Reality of the Court Environment

Courts are different. They do not initiate performance improvements for the same reasons and do not follow the same routes to higher performance. As we recounted in our second article,2 the Scottsdale City Court was motivated to improve its performance assessments and reporting in response to concerns about its operations that were raised by both the public and government officials (the Social Value Perspective). In Virginia, various circuit courts confronted issues of increasing delay or docket and case scheduling that indicated inefficient and unproductive case processing (the Internal Operating Perspective). Other courts have started from a desire to improve customer service or address concerns about access and fairness (features of the Customer Perspective).

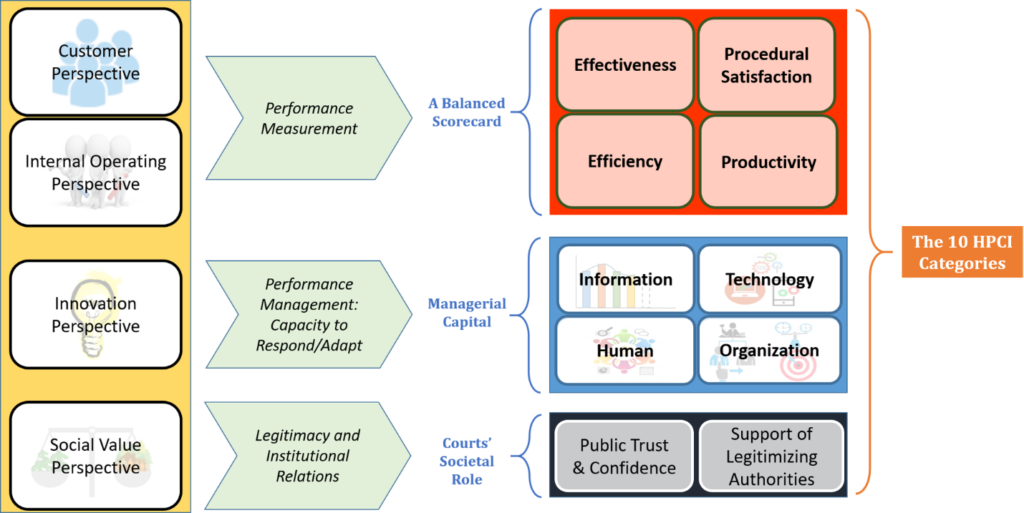

A court need not have an immediately apparent challenge to be motivated to improve; one might simply have a general desire for higher performance and seek some additional information that might help it focus its efforts. A broad assessment instrument such as the High Performance Court Self-Assessment (also known as the “High Performance Court Inventory,” or HPCI)3 can identify perceived strengths and weaknesses across ten categories covered by the four perspectives (see Figure 1). A benefit of using a tool like the HPCI is that it not only informs a court about how its performance is perceived but also offers insights into a court’s managerial resources (the Innovation Perspective)—the organizational, technological, human, and information capital, which significantly define a court’s capacity to achieve performance goals. A court might need to target its managerial capital before or in parallel with performance improvement efforts.

So What?

So, what does all this mean for any given court? How can someone use the concepts of the Framework to begin, and ideally sustain, an improvement initiative? What about cultural attributes that may inhibit change? In this article, we offer Framework-consistent approaches that answer how a court may go about achieving higher performance.

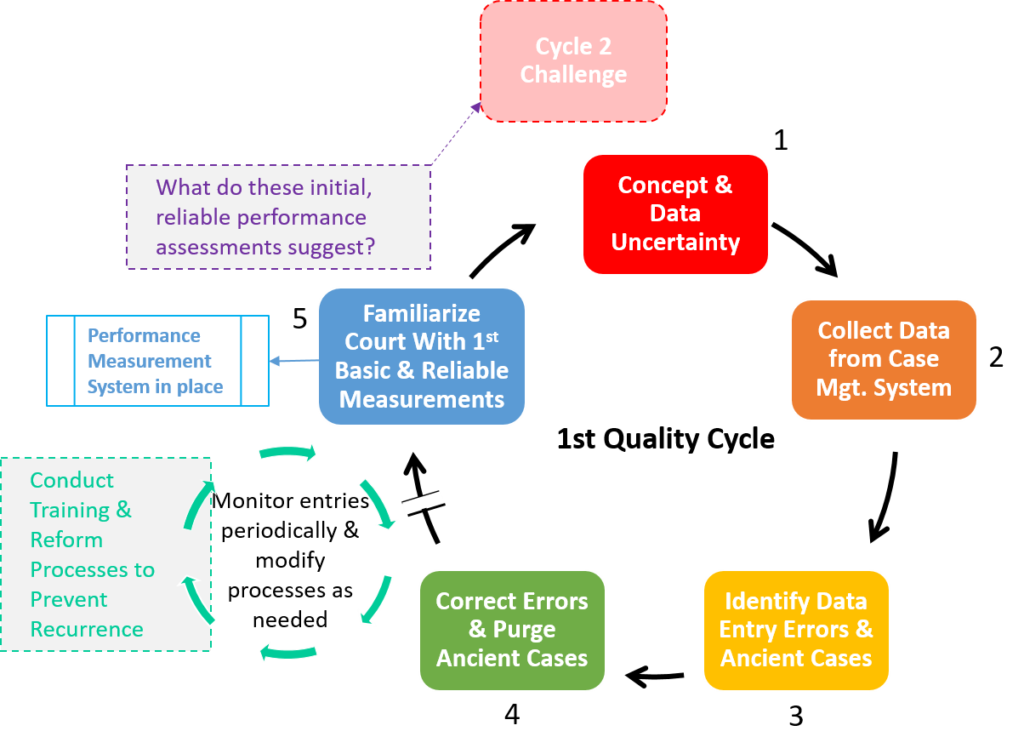

Most improvement efforts begin with the recognition of a performance challenge. Whether a court already faces an apparent challenge or identifies a priority area for change through a structured self-assessment, such as the HPCI, there are practical, graduated methods for improving performance. Selecting what process to use in facilitating improvements should be an early court decision. The Framework provides a change management methodology in the Quality Cycle (see Figure 2), and this article will discuss approaches referencing its process steps; however, there are other, similar change management processes that a court might follow. Fundamentally, any improvement effort needs to be clear and workable, and those qualities are found in the Quality Cycle. From a practical standpoint, these early stages are when the proponents of change must secure buy-in from senior court leadership and determine the roles to be played by the judges and other stakeholders.

In the Quality Cycle, after a court identifies its initial challenge, it must learn more about the scope, causes, and possible solutions to the performance issue. Among the first actions would be efforts to understand the court’s environment, including influences on the court’s decision-making processes and factors that may be driving the need for change. Collecting data relevant to the challenge is therefore necessary. Reliable performance measurements addressing one or more aspects of the Framework’s Balanced Scorecard expand the court’s information capital, providing a basis for better understanding the performance challenge. Analysis of the performance data may point to the need for additional data collection, either from repetition of the same measurements or from ones related to other perspectives, including those associated with the court’s other managerial capital. Assessment and adaptations that account for court culture may be necessary.4 Ultimately, the analysis provides the basis for problem solving, planning, and strategies for responsive action. Implementation of action plans often require adjustments to organizational structure, training of court personnel, and changes in the use of technological resources. Ongoing evaluation of strategies through performance measurements may point to the need for strategy modifications. Ultimately, through one or more iterations of the cycle, the challenge can be met. Generally, by completing the process, a court should improve its overall capacities for further performance improvement, particularly by improving human and other managerial capital and court culture.

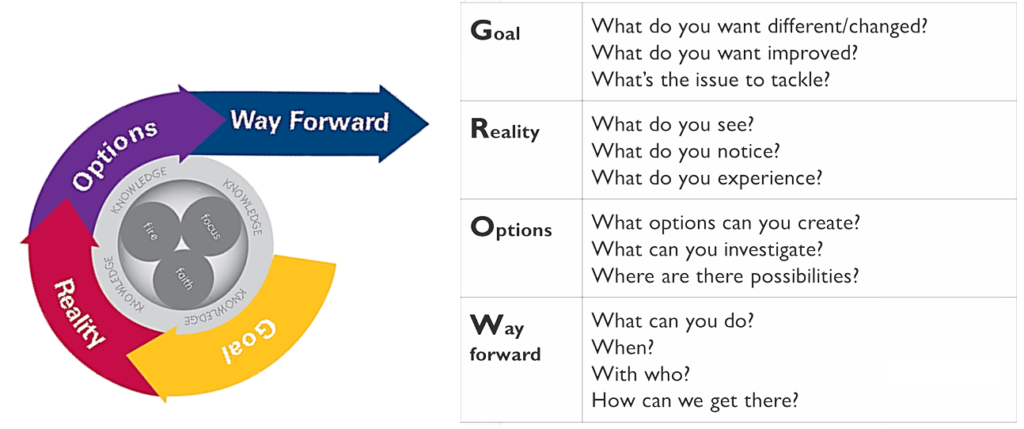

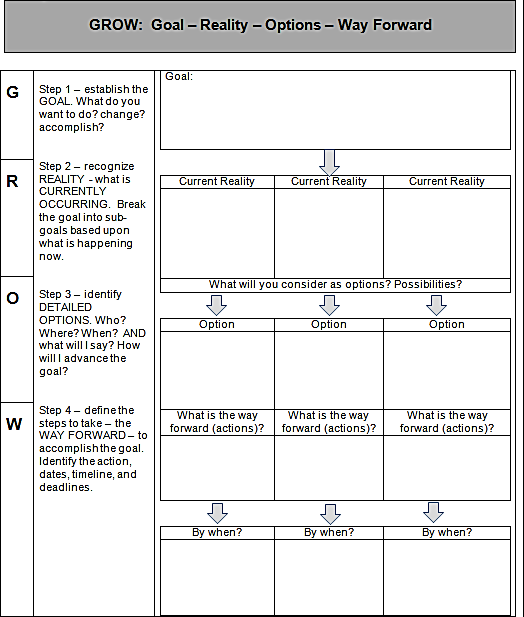

Not surprisingly, successful approaches to change share common features. Expanding on the Quality Cycle idea, another approach that we have experienced uses concepts from a book on coaching. The Goal-Reality-Options-Way Forward model (or GROW)5 represents steps a leader can employ to accomplish change: identify the goal, assess the reality, consider options, and declare the way forward (see Figure 3).

The key message for court leaders is that achieving high performance is an ongoing process. When considering any change or innovation, court leaders should consider their actions as part of an ongoing activity. They need a strategy and a plan. One example of a planning structure is noted below (see Figure 4).

Examples of Approaches

In our second article, we identified courts that have employed elements of the Framework and detailed the actual benefits that resulted. In our Scottsdale, Arizona, and Virginia examples, the improvement challenges and approaches were different, confirming that there are multiple ways to make use of Framework concepts. We describe a few approaches below.

Linking Court Performance Metrics to the Framework’s Concepts for Outcomes

When a court starts using operational performance metrics, it may be difficult to arrange and present them in a way that is easily understood and received and not too overwhelming. Such difficulties can undermine managerial responses to performance challenges (the Innovation Perspective) and external perceptions of how well a court is operating (the Social Value Perspective). The way a court chooses to talk about performance data can, therefore, make or break the court’s openness toward data utilization about how a court is performing.

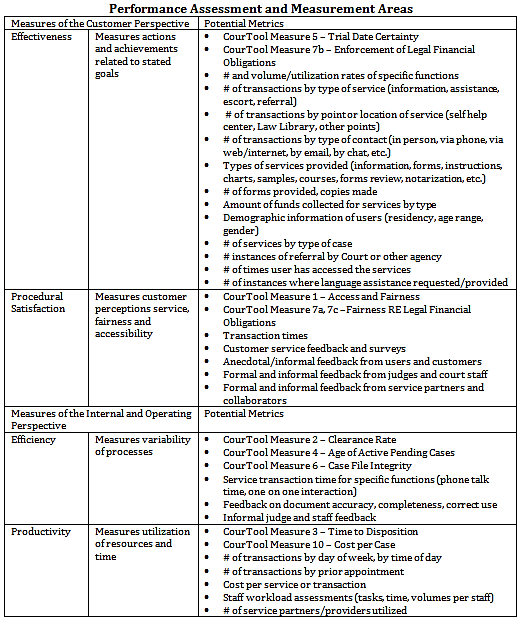

Figure 5 illustrates how a court can arrange and include information about how well it is achieving effectiveness, efficiency, procedural satisfaction, and productivity. The display couples high performance concepts with real court performance measures. These four performance categories are outlined in the Framework and can serve as categories or target areas for a court to present its performance information. There is nothing mysterious about these categories, but they tie to a court’s ability to use court-based data to inform non-court individuals about court performance and outcomes.

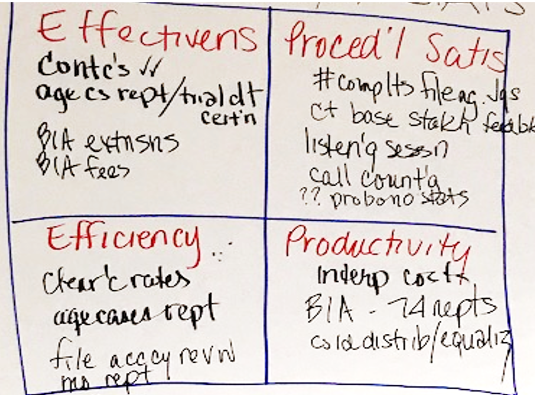

At first glance, the detail presented in Figure 5 can appear overwhelming. Experience has shown, however, that a court can rather easily distill the detail into more concise and relevant metrics for its particular needs. The practice of arraying court performance measures in a grid with broad categories (e.g., effectiveness, procedural satisfaction, etc.) has proved to be a helpful exercise when working with courts on court performance and accountability. It gives an organized structure to think about what their performance measures are telling them about their courts’ performance and what challenges they may choose to confront. Such an exercise is copied below (see Figure 6). Framework concepts of measuring effectiveness, efficiency, procedural satisfaction, and productivity are used to prompt leaders to identify which of their currently collected data provide information in each category.

Using Framework Perspectives When Reporting on Court Operations

Courts often issue annual or periodic reports about accomplishments. These reports commonly contain charts or tables with aggregate numbers of cases filed and numbers of cases closed. These aggregate data tell a story, but there is more to tell about how effective a court has been. Because operations of courts are somewhat mystifying to those not familiar with court processes, court leaders need to get creative in explaining what courts do and how the organization has achieved desired goals. In the limited-jurisdiction Scottsdale City Court profiled in our second article, the challenge was to change perceptions of the court in a turbulent time; demonstrate how the court and its leadership could be accountable and report on court operations; and illustrate the purpose of a court (to conduct certain activities and be transparent about operational outcomes via measures).

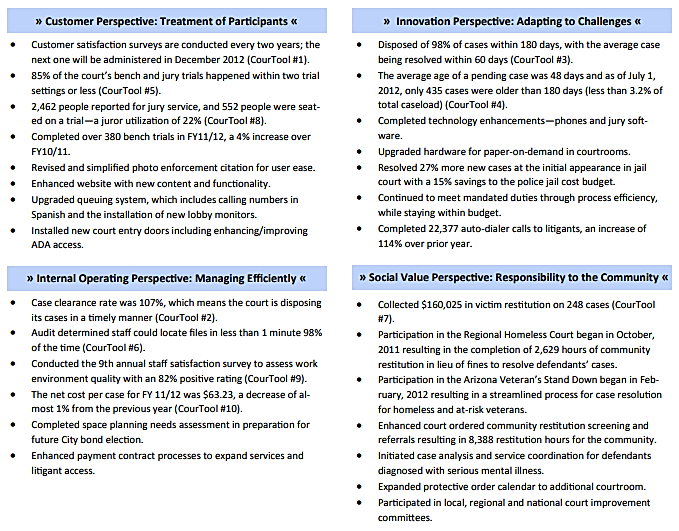

Determining Scottsdale’s way forward was helped by its leaders’ familiarity with innovations and practices occurring in courts around the country. They realized that the court would benefit from using nationally known and vetted concepts (e.g., the High Performance Court Framework and the CourTools measures) to frame the work of the court. The chief judge was apprised about the actions underway and delegated the work to the court administrator. A team of committed and senior court staff supported the work, bringing continual and better ideas to the table. Discussions were ongoing about how the process was working and what the data (with and without blemishes) were revealing; any inaccuracies in the data were accepted and noted where possible. Using the Framework’s concepts of different perspectives, the court organized its annual-report content using performance data and descriptive narrative presented in these four perspectives (see Figure 7).

This sample structure using the Framework concepts and CourTools measures was shown in our second article (see Figure 8). It reinforces the benefits of using Framework ideas to mention again this use of these four perspectives taken directly from the Framework: customers, innovation, internal operations, and social value. In this use of Framework ideas, performance metrics (numbers) are combined with descriptors and narrative that explain what the court had accomplished to be responsive to customers, to demonstrate innovative practices, to focus on internal operational excellence, and to serve the community.7 The leaders of the Scottsdale court recognized that there was a degree of risk in visibly connecting the court’s performance with concepts used in other courts, but the benefits to improving upon outdated reporting methods were worth that risk. The end result was increased comfort and conviction on the part of the courts’ leaders—the chief judge and court administrator—that using court-based concepts and practices made a difference. It involved using the Framework and the court performance measures, and having faith that the action would demonstrate solid court leadership.

Using Framework Concepts to Address Performance Challenges

Court leaders, who are critical to initiating and sustaining improvements, may have a sense that some aspect of their operations needs improvement, but they can be reluctant to jump into using performance measures due to the risk of inaccuracies. Furthermore, and more importantly, court personnel may not feel able to talk intelligently about court work and outcomes.8 As discussed in our second article, several Virginia circuit courts have successfully used Framework concepts to attack delay and improve the docketing of cases. Notwithstanding the different issues that each court initially faced, each one soon discovered the need and undertook a major effort to improve data integrity and timeliness with assistance from a team of experts from the state court administrative office, who reinforced lessons related to data-entry practices and educated leaders and staff about basic performance measurements. Tailored use of the quality cycle was immediately implemented wherever improvement or effective change was needed (e.g., see Figure 9). Of central importance was the integration of the use of data to inform every step of the change process and the building of court capacities to use and interpret data continuously.

It is important to emphasize this connection to capacity building. In the course of the sample quality cycle above, a court can improve several forms of managerial capital: information (data reliability), organization (data-entry processes for case management), and human (understanding of some basic performance measurements). Among Virginia courts, there has also been increased understanding and use of features or capabilities of the case management system (technology capital), while staff have become more engaged in discussions of court performance issues (see Figure 10), changing court culture. The critical result is that a court becomes capable of a more complex cycle of analysis and action for court improvement.

After improving the quality of their case data, Virginia courts that started with the need to reduce delay progressed to considering performance metrics in each quadrant of the Framework’s Balanced Scorecard and then tailoring CourTools measures to their particular needs. Once a court began to ask how it might effectively implement change, it was also inexorably led to consider areas of managerial capital, especially human capital. It is no coincidence that CourTools Measure 9, Court Employee Satisfaction, connects directly to human-capital-resource development. Courts that needed to improve case scheduling, again after an initial data improvement effort, found that they needed, and wanted, to focus on various managerial capital areas—especially human-capital development and technology.

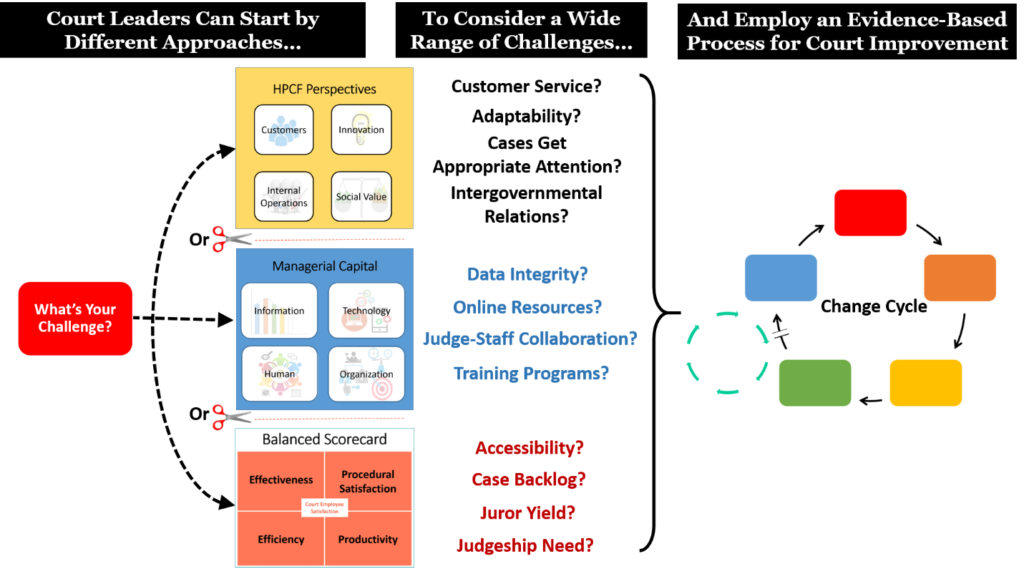

Conceptual Connectedness Allows Versatile Approaches

As courts gain experience using the concepts of the Framework, they naturally begin to see connections with and talk about court customers and customer service issues; how to improve internal operations; how to innovate; and how to increase, improve, or more effectively share their role with the community—the essence of the four Framework Perspectives. Here is the key lesson: no matter where in the Framework a court begins to focus on a specific problem, the Framework itself presents an effective, dare one say natural, pathway to more comprehensive and effective court improvement. This lesson is summarized in Figure 11. No matter the challenge, no matter where a court begins, that court can use the areas of the Framework to guide successful improvements if the use of data informs every step. Furthermore, areas of the Framework can be “cut apart” and used alone or in combination with others, especially as court efforts continue.

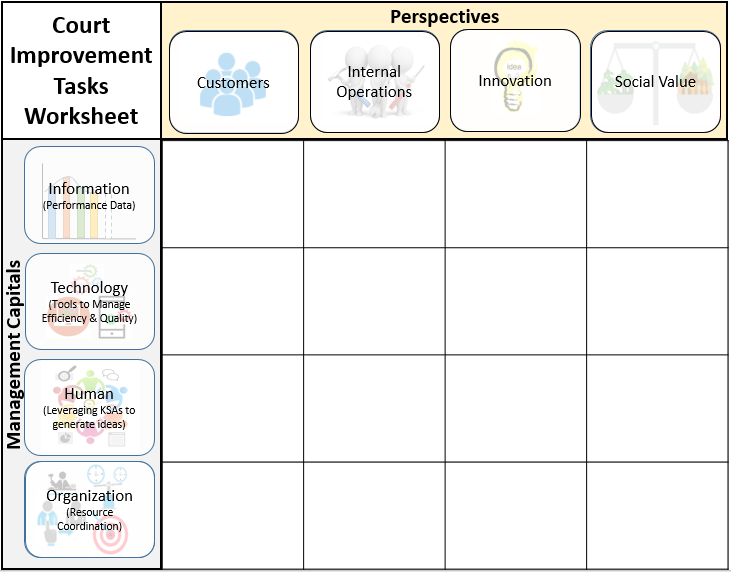

Even as Virginia circuit courts have begun to use the Framework and have gained experience with it, other court management uses are also becoming evident. Virginia’s general district and juvenile and domestic relations district courts are now beginning to use an integrated Framework approach to improve internal court management. In this instance, “integrated” means the use of a Framework “matrix” (see Figure 12) that quickly helps a court diagnose current problems, for example, with customer service, and then begin to develop plans to improve across managerial capital areas or other Framework perspectives. This “matrix”—in reality a simplified version of the Framework—is used as an actual assessment and planning tool with the management teams in specific courts to help them visualize connections among performance concepts. Initial reactions to this approach have been positive and optimistic.

The Framework is not just a tool for court operational improvement, but, especially to the degree that a court incorporates data-informed decision making into its routine processes and uses a goal-driven approach such as that presented by the GROW model, the HPCF becomes an excellent doorway to strategic thinking and strategic planning for a court. In such contexts, court leaders should keep in mind the fundamentals for successful change efforts that are discussed at the beginning of this article and remember the seven strategies below that court leaders should consider to build and sustain high performance:

- Share the vision—translate vision to activity; articulate and sell the vision.

- Explore the culture—manage roadblocks and change processes.

- Abandon the lone-ranger approach—use leadership persuasion and seek court-wide agreement.

- Focus on the customer—remember the court customers and users.

- Get administrative staff involved—use court-wide performance objectives.

- Promote collegial discussion—make use of communication and collective action.

- Share results—build support via feedback and publication of performance outcomes.9

The Framework provides a structure for the ongoing application of such lessons.

Conclusion

Despite the great amount that has been learned over the last 50 years about what high performance means in courts, few courts manage to achieve it. Our profession has not done enough to develop institutional capacities or communicate effective approaches to performance improvement. We have seen how the High Performance Court Framework provides guidance by which any court can do both. The Framework is sensible and flexible, allowing courts to start from different perspectives to identify challenges and demonstrating how courts can draw upon many innovations and concepts to make evidence-based decisions about how to resolve those challenges. The Framework recognizes the importance of committed leaders and of engaged employees, without which improvement is unlikely and even past progress may be lost. By using a change management process like the Framework’s Quality Cycle, the GROW model, or other action-planning practices, courts are encouraged to approach change in an ongoing, incremental manner, developing institutional capacities and adaptable cultures for progressively more significant improvements through each succeeding cycle. Whatever your court’s current status, you can improve its performance. Many approaches are open to you employing the Framework’s concepts. The first step to high performance is just to get started.

Questions for Consideration

- Are you up for the challenge?

- How and where can you use the Framework concepts?

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

This article was a collaboration among Janet G. Cornell, court consultant and retired court administrator in Arizona; Cyril W. Miller, Jr., Ph. D., and Kenneth G. Pankey, Jr.—director of judicial planning and senior planner (respectively), Department of Judicial Planning, Office of the Executive Secretary, Supreme Court of Virginia.

- See Kenneth G. Pankey, Jr., Anne E. Skove, and Jennifer R. Sheldon, Charting a Course to Strategic Thought and Action: Developing Strategic Planning Capacities in State Courts (Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts, 2002), pp. 18-23.

- Janet G. Cornell, Cyril Miller, and Kent Pankey, “The High Performance Challenge: Courts’ Experiences with the High Performance Court Framework,” Court Manager 34, no. 4 (2019).

- The High Performance Court Self-Assessment tool may be made available upon request from the National Center for State Courts, Research Division, phone 1-800-616-6164.

- As we explained in our first article, Janet G. Cornell, Cyril Miller, and Kent Pankey, “The High Performance Challenge: Concepts and a Call to Action,” Court Manager 34, no. 3 (2019), differences in court cultures can require different strategies for resolving otherwise similar performance challenges. The Framework draws upon earlier findings described in Brian J. Ostrom et al., Trial Courts as Organizations (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2007) to offer methods for understanding court culture and for diagnosing and, when appropriate, changing culture. Not every change effort will require significant attention to culture.

- In the 1980s, Alan Fine developed the GROW Model with Graham Alexander and Sir John Whitmore. The GROW Model is constructed upon the insight that breakthrough performance comes more often, not from acquiring additional knowledge, but from removing internal interference that allows a person or organization to act on what they already know. This insight is consistent with our contention that courts already have access to a great deal of knowledge about high performance, but court leaders do not know how to act on it. The version of the GROW Model graphic used here is from Alan Fine and Rebecca R. Merrill, You Already Know How to Be Great (New York: Penguin, Random House, 2010). For more information, see www.insideoutdev.com.

- Content adapted from the National Center for State Courts’ Framework materials (see “High Performance Courts Framework”). A variation of this chart was initially published in Janet G. Cornell, Felix F. Bajandas, and Nathan Hall, Shared Self Help Center Assessment and Planning for the Second Judicial District Court, Washoe County, and Reno Justice Court (Denver: National Center for State Courts, 2018).

- See the full Scottsdale City Court Fiscal Year 2011/2012 Executive Summary.

- See Janet G. Cornell, “Court Performance Measures: What You Count, Counts!” Court Manager 29, no. 1 (2014).

- Brian Ostrom, Roger Hanson, and Kevin Burke, “Becoming a High Performance Court,” Court Manager 26, no. 4 (2011-12).