Court leaders can face challenges when implementing and institutionalizing caseflow management practices. Generational influences and preferences may impact success. This article considers caseflow management practices, influences on success, and suggestions about caseflow techniques that make use of generational tendencies.

Caseflow Management Practices

Many sources explain caseflow management practices and techniques.1 Typical best practices and management techniques are based on the following:

- goals, leadership, and clear vision

- calendaring, case assignments, scheduling, meaningful and firm events

- early, continuous, and regular oversight and control of case progress

- dispute resolution practices and early case resolution steps

- collaboration and outreach—internally and externally

- communication, education, and sharing

- use of performance data and information

Influences on Success in Caseflow Management

Why have courts struggled to implement caseflow practices? The answer may relate to several influences, which affect the practice of caseflow management. Those influences include:

Competition

A variety of important topics and programs command court leaders’ attention. These include matters such as cybersecurity, continuity of operations, cultural and linguistic needs, and relationships with justice partners. In a 2018 compilation of surveys, court professionals identified topics court leaders consider important for the next ten years:

- dealing with executive and legislative branch involvement in court practices and policies;

- high turnover in court staff and changes to organizational memory; and

- records management with new and increasing technology advances.2

Programs

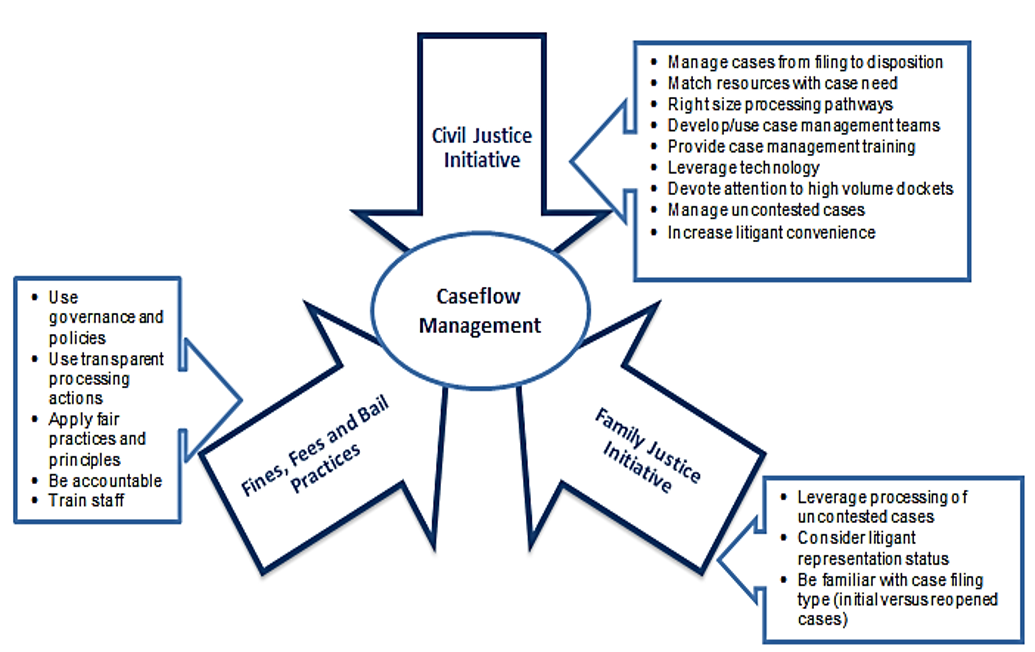

Programs like reform initiatives can distract court leaders from caseflow management. These initiatives can at the same time underscore the importance of handling cases. Renewed attention to caseflow management is a by-product of such programs. Three notable reform programs include the Civil Justice Initiative, the Family Justice Initiative, and reforms in fines, fees, and bail practices.3 Each has a direct or indirect impact on caseflow management techniques. Court leaders may need to evaluate caseflow management techniques and revamp or realign them to implement and support programs and reforms.

Focus

Caseflow management success may be hampered by a lack of priority and focus. When Ernest Friesen wrote about the need for a “Prescription for Renewal” on caseflow management, he noted, “Achievements of the 1980s have slipped away.”4 Causes of slippage may be changes in court leadership and new judges, failure to make timely case resolution a priority, and insufficient training. Court consultant and author Alex Aikman has noted that courts have faced a “systemic failure” from lack of focus on caseflow management practices. He asserts that court leaders should embrace and apply caseflow management practices.5

Consider the Generations

Much has been written about dealing with different generations, each possessing distinct perspectives and values within the workplace. Generations have specific traits and preferences based on life experiences and societal influences.6 Listed below are descriptors about select generations, denoting variations in values and affinities for each group.

| Veterans, Traditionalists, Matures (1925-1945) | Respect hierarchy, possess loyalty, expect predictability and stability |

| Baby Boomers (1946-1964) | Use consensus, prefer face-to-face meetings |

| Gen X (1965-1980) | Desire independence, like choices, are self-driven |

| Millennials/Gen Y (1981-1995) | Are savvy about and comfortable with technology, need information and feedback, desire quick access |

| Gen Z (1995 and later) | Prefer instant feedback, are connected and plugged in, are comfortable with transparency |

Generational preferences invite considerations of difference not only among employees but also among the expectations of court users. These preferences impact success when implementing and sustaining caseflow management techniques. So, how should court leaders craft caseflow management techniques and court processes to appeal to different preferences and to leverage generational tendencies?

Suggested Caseflow “Generational Practices”

Court leaders familiar with generational differences should

conceptualize caseflow practices in consideration of generational preferences.

This entails determining how caseflow practices can support different

preferences. The illustration below suggests select caseflow actions, linking

them to generational characteristics.

Aligning Caseflow Techniques with Generational Preferences

| Generational Traits | Suggested Caseflow Actions |

Respect hierarchy|

Explain and illustrate the underlying “hierarchy” or structure and expectations for caseflow practices by litigants.

| |

| Possess loyalty | Strive to explain and demonstrate why the court adheres to predictable, consistent, and procedurally fair practices—for the benefit of being “loyal” to published practices/processes and ensuring fairness. |

| Expect predictability | Be consistent and adhere to published and known policies and procedures. Inform self-represented litigants about practices and expectations. |

| Use consensus | Use, to the degree possible, public and litigant input and feedback on processes. This may include access and fairness surveys and feedback mechanisms. |

| Prefer face-to-face meetings | Offer structured meetings and interactions for self-help to litigants (e.g., use of self-help centers, information sessions, or legal assistance clinics). |

| Desire independence | Provide information and instructions to litigants to provide choices in acting on cases. |

| Like choices | Create and provide a “menu” of options for litigant action to comply with case handling. |

| Self-driven | Inform litigants of deadlines and actions required and expected. |

| Savvy with technology Connected and plugged in | Use technology for all phases and aspects of case handling and in particular for public use. |

| Seek information and feedback | Create processes for the court, via judges and court staff, to obtain public/user feedback on how and if they understand what is expected of them and identify channels to provide information to users. |

|

Seek quick access Prefer instant feedback | Establish caseflow mechanisms for speedy status and feedback to litigants about case events, actions, and outcomes. |

| Look for transparency | Demonstrate, to the degree possible, accountability and transparency in practices that underpin caseflow management, data and statistics about operations, and outcomes of court work. Disclose clear information. |

Conclusions

Addressing caseflow practices with generational preferences may make a difference and help court leaders achieve greater success in sustaining caseflow practices. How can you get started?

- Consider the influences of different generational groups. Get familiar with how others have different perspectives, values, and needs. Become familiar with court users and their needs.

- Be familiar with caseflow management techniques and practices. Become aware of techniques that have been proven to work.

- Examine where and how court users and litigants “touch” or interact with court processes and be informed of service locations and delivery (e.g., via phone, on-site, over the Internet, via documents, in a courtroom, etc.).7

- Learn about current and desired service practices employed by courts to interact with litigants (basic customer service or providing of assistance to self-represented litigants).8

- Evaluate how your court can implement case-monitoring and caseflow techniques in a way which understands and leverages preferences driven by generational views. Identify which items from the “menu” of caseflow techniques can be responsive to generational preferences.

- Consider continually asking questions and evaluating processes and practices. Measure how the court is performing and responding to users. Publish information about results and outcomes of “new” practices.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Janet G. Cornell is a NACM past

president and retired court administrator. She is currently a court consultant

and presenter. As a former court manager, she has experience practicing and

teaching caseflow techniques. She can be reached at jcornellaz@cox.net.

- Caseflow management sources include Maureen Solomon, Caseflow Management in the Trial Court (Chicago: American Bar Association Commission on Standards of Judicial Administration, American Bar Association, 1973); Barry Mahoney, Changing Times in Trial Courts: Caseflow Management and Delay Reduction in Urban Trial Courts (Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts, 1998); William Hewitt, Geoff Gallas, and Barry Mahoney, Courts That Succeed: Six Profiles of Successful Courts (Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts, 1990); David Steelman, John Goerdt, and James McMillan, Caseflow Management: The Heart of Court Management in the New Millennium (Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts, 2004); Alexander Aikman, The Art and Practice of Court Administration (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2007); National Center for State Courts, Institute for Court Management, course on “Fundamentals of Caseflow Management,” 2012; and the National Association for Court Management’s Core (Core Competency) on “Caseflow and Workflow,” 2016, available at http://nacmcore.org.

- Philip Knox and Peter C. Kiefer, “Where Are Courts Going in the Next Ten Years: Ten Things to Know,” August 26, 2018. The article summarizes and prioritizes survey responses from over 1,200 court professionals obtained from annual surveys conducted from 2013 to 2018.

- See additional information at the Civil Justice Initiative, Family Justice Initiative, and Fines, Fees and Bail Practices Resource Guide.

- Ernest Friesen, “Caseflow Management: A Prescription for Renewal,” Court Communique 9, no. 2 (2008).

- Alex Aikman, “An Essay on Restoring Caseflow Management to the ‘Heart of Court Management,’” Court Manager 30, no. 2 (2016).

- Sources used for generational traits include Cam Marston, Motivating the “What’s in It for Me?” Workforce: Managing Across the Generational Divide (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2005); Wall Street Journal, “How to Manage Different Generations,” How-To Guide; Julia Lewis, “How to Deliver Exceptional Service to Four Generations of Customers,” Provide Support Blog, April 16, 2015; Center for Generational Kinetics, “Five Generations of Employees in Today’s Workforce,” 2016; “Connecting with the Generations,” training course by the City of Phoenix, May 2018; and Harvey Mackay, “It’s Now Time to Welcome Generation Z,” Arizona Republic (May 20, 2019): 12A.

- For the concept of “touches,” see Janet G. Cornell, “Court Performance Measures: What You Count, Counts,” Court Manager 29, no. 1 (2014).

- A variety of sources and publications provide information about services and access for self-represented litigants (e.g., the National Center for State Courts’ Justice for All and Harvard’s Access to Justice Lab websites), and many states have access-to-justice commissions.