Caseflow management is a court responsibility, which benefits from ongoing attentiveness. Caseflow management practices involve efforts for monitoring and overseeing case progress while managing any case backlogs. Monitoring steps occur (optimally) from case initiation through trial, adjudicatory actions, and final disposition. Caseflow-monitoring activities can even extend to any post-disposition case events and oversight by a court. This article illustrates the case stages.

Court reform developments led the way to consideration of caseflow management as a primary court leadership responsibility. Among the stimuli and motivations for reform were:

- attention to and avoidance of court delays contributing to perceptions of court inefficiencies;

- development and rise of court management as a profession responsible for day-to-day oversight of court operations;

- emergence of caseflow principles, techniques, and procedures to support practices;

- focus on accessibility to courts, including guidelines, policies, and schedules; and

- consideration of order enforcement and the reliability of court functions1

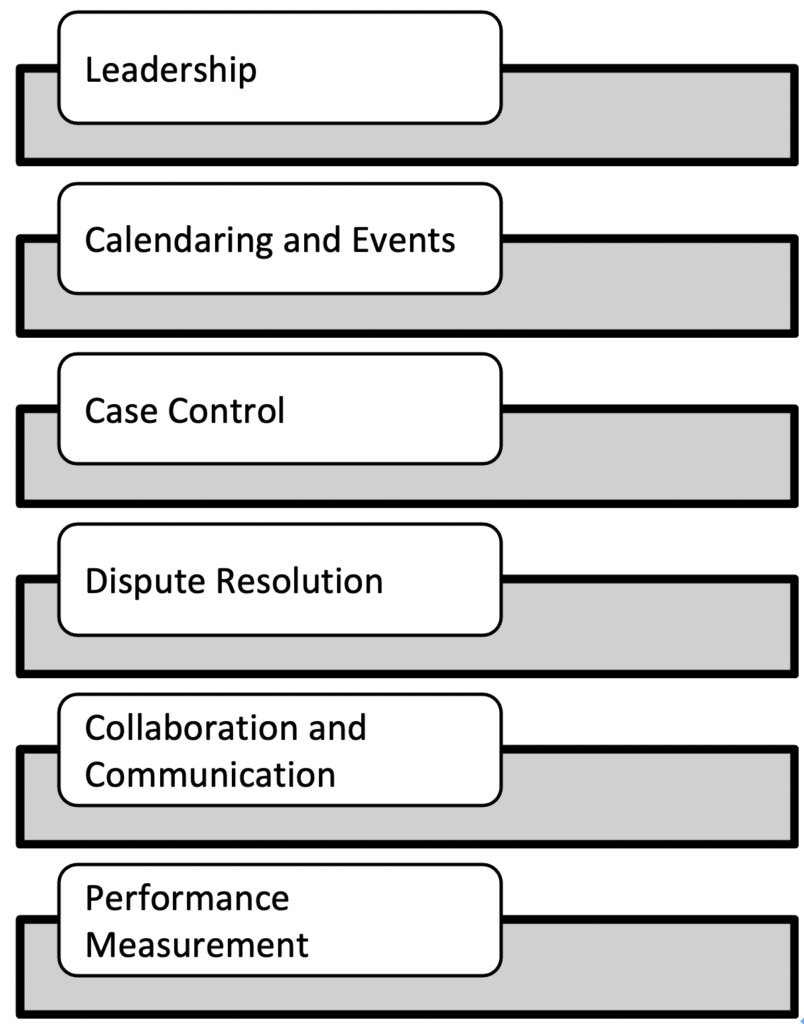

Conditions for success with caseflow management include planning, ongoing commitment, a system-wide approach, review of current processes and case inventory, and institutionalization of program elements.2 Caseflow management best practices have been published for over 40 years. Among the known and proven techniques are:

- leadership direction, goals, and a clear vision of what is desired;

- case assignments, calendaring and scheduling, meaningful and firm events;

- early, continuous, and regular oversight and control of case progress;

- dispute resolution and early case resolution steps;

- collaboration, outreach, communication, education and training (internally and externally); and

- performance data and information3

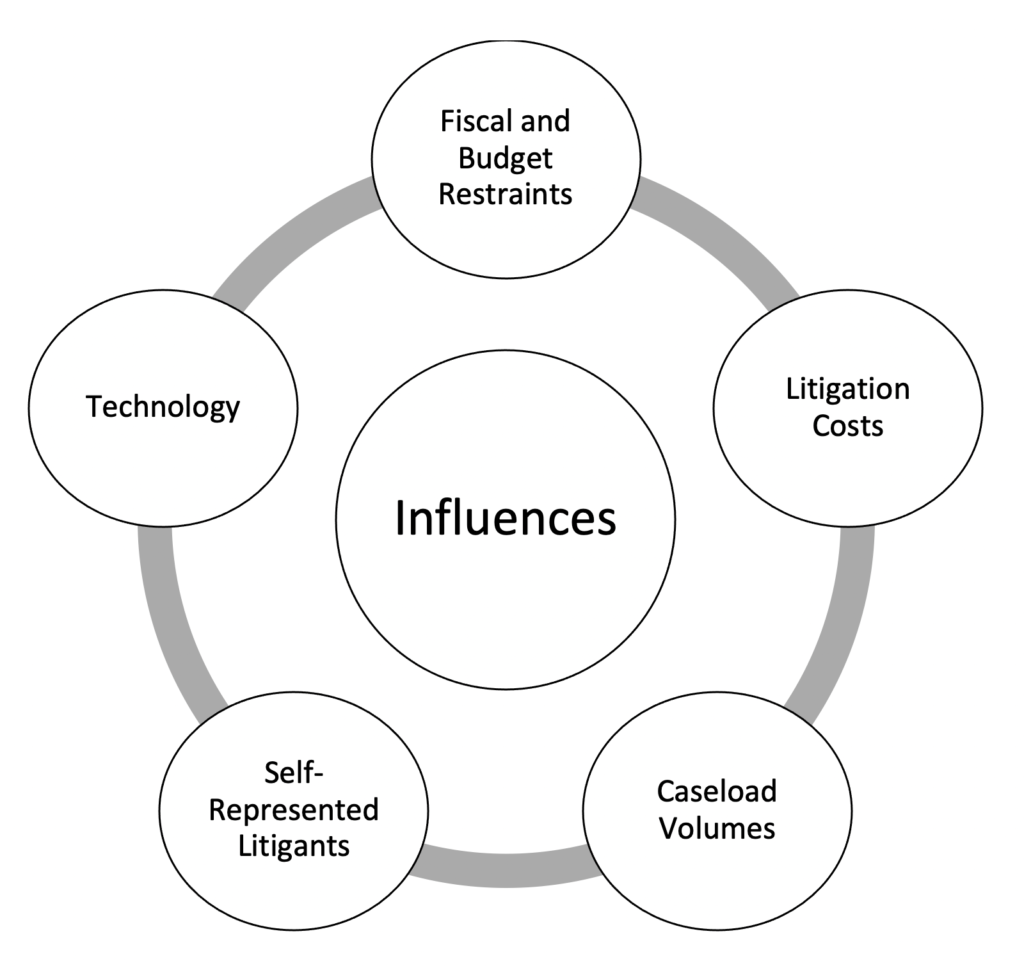

There are no shortage of reasons why practicing caseflow management is challenging. As noted by the Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System (IAALS), difficulties faced by courts include influences, which are not inconsequential. They include fiscal, budget, and funding issues; litigation costs and influences on litigant access to the court; changes in caseload filing volumes; large numbers of self-represented litigants; and technology changes and influences.4

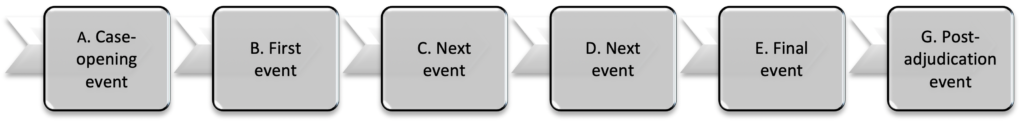

To overcome such challenges and develop the conditions for successful caseflow management, a court manager should foster attentiveness to caseflow techniques. Such attentiveness begins by developing familiarity with the order and specific actions that can be anticipated for all phases of case handling at one’s court. All courts have a predictable sequence for events taking place during the life of a case. These phases of activity and their sequence are typically:

- Case opening, filing, or the first action initiating the case.

This phase may involve a civil complaint or petition or a criminal-charging document or indictment. - The early, first, or initial court event.

A possible event in this phase might be the opening conference, hearing, arraignment, or initial appearance. - Case preparedness or case progress events.

This phase may include a case management conference, omnibus hearing, discovery or disclosure conference, trial readiness event, status conference, arbitration/mediation/settlement event, or motions consideration. - Pretrial or final trial readiness event.

A trial readiness discussion, pre-case management conference, final settlement event, or trial management discussion are common events of this phase. - Trial.

Activity in this phase may be a bench or jury trial or some other event adjudicating and providing a final ruling on the case to move it to final disposition. - Post-adjudication or post-disposition.

This phase is associated with any activity after entry of judgment, post-adjudication, or final disposition events, including actions such as case review, compliance monitoring, or other reporting.

Typical case phases can be mapped or charted, indicating high-level stages within the life of a case. The chart below illustrates summary or simplified phases, without regard to a particular type of case.

Using the phasing concept, if we combine the illustration of caseflow management best practices and techniques and arrange them for each stage in the life of the case, we can develop a chart of what can be done to practice effective caseflow. Each caseflow action or technique represents something tangible, actionable, and capable of being institutionalized in a court. When courts use these techniques, they will be practicing effectual caseflow management.

In addition to best practices specific for each case phase, there are best practices which span all phases. These practices include leadership; collaboration, consultation, and coordination with justice constituents and system partners; training and education for those internal and in-partnership with the court; and the use of information and data. The chart below illustrates the generic case phases within the life of a case and provides possible caseflow actions appropriate to each phase. Actions transcending all phases are noted at the bottom of the chart.

As a means toward improving attentiveness, illustration of these case stages and sample caseflow practices provide guidance for events throughout a case’s life. Courts can use this chart as a checklist of considerations and actions for each stage of case handling, supporting the performance of fundamental caseflow management responsibility. Courts can also evaluate existing caseflow practices at each case stage and determine how and where any additional practices need to be implemented. Therefore, the chart can be used to prompt utilization of caseflow actions.

To fully apply these ideas, a court will need to exercise leadership. This leadership will be best exemplified by creating a caseflow governance structure; establishing caseflow objectives and direction; performing case evaluation and case supervision; collaborating with and training stakeholders and court personnel on goals; and measuring outcomes.5

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Janet G. Cornell is a past president of NACM, and a retired court administrator, having served over 35 years in the Arizona courts. She is currently a court consultant, presenter, and author. She may be reached at jcornellaz@cox.net.

- David C. Steelman, John A. Goerdt, and James E. McMillan, Caseflow Management: The Heart of Court Management in the New Millennium (Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts, 2004), pp. xi-xvi.

- Id., pp.127-34.

- Janet G. Cornell, “Aligning Caseflow Management Practices with Generational Preferences,” Court Manager 35, no. 1 (2020).

- Brittany K.T. Kauffman and Natalie Anne Knowlton, “Redefining Case Management,” Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, IAALS, University of Denver, April 2018, pp. 7-10.

- The author thanks caseflow author and expert David C. Steelman for sharing email correspondence and references on emerging caseflow topics. The author also offers appreciation to Kenneth G. Pankey, Jr., senior planner with the Supreme Court of Virginia, for editorial review of this article.